Words by Jane Crowther

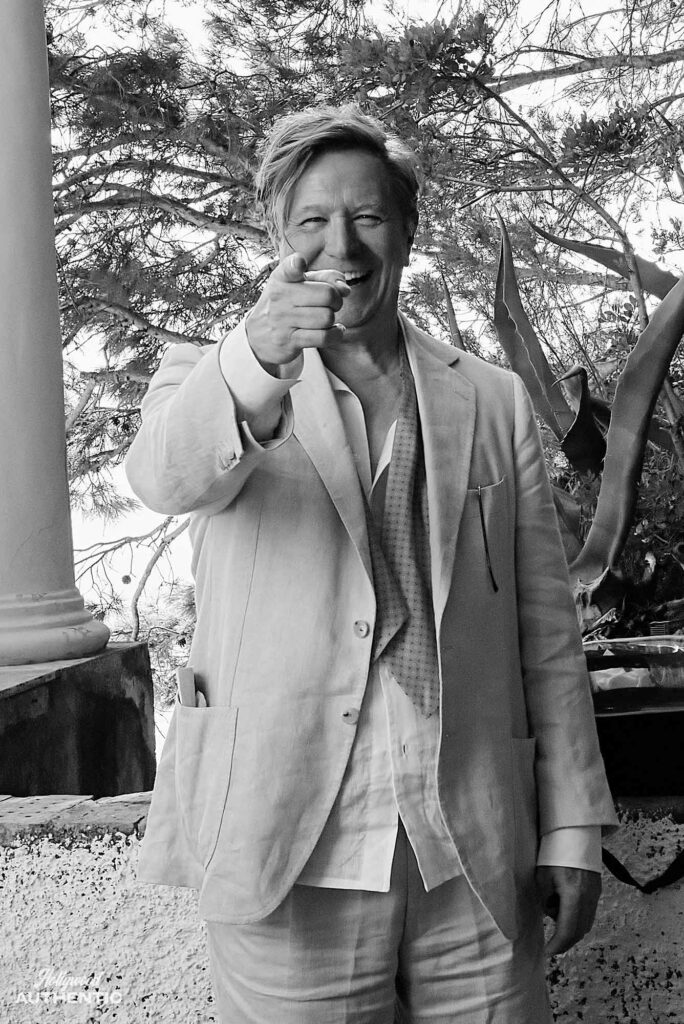

Photographs by Greg Williams

Awards season closed with an Academy Awards that was a who’s who roster of past recipients and powerhouse Hollywood talent. Twenty previous winners announced the four acting categories – each group leaving the stage as a gang with their latest inductee, a newly-formed club hanging out stage-side after each award. The community at the heart of acting was celebrated in this way, and also in a moment when the backstage team were brought centre-stage to celebrate the solidarity shown across the industry during the strikes earlier this year.

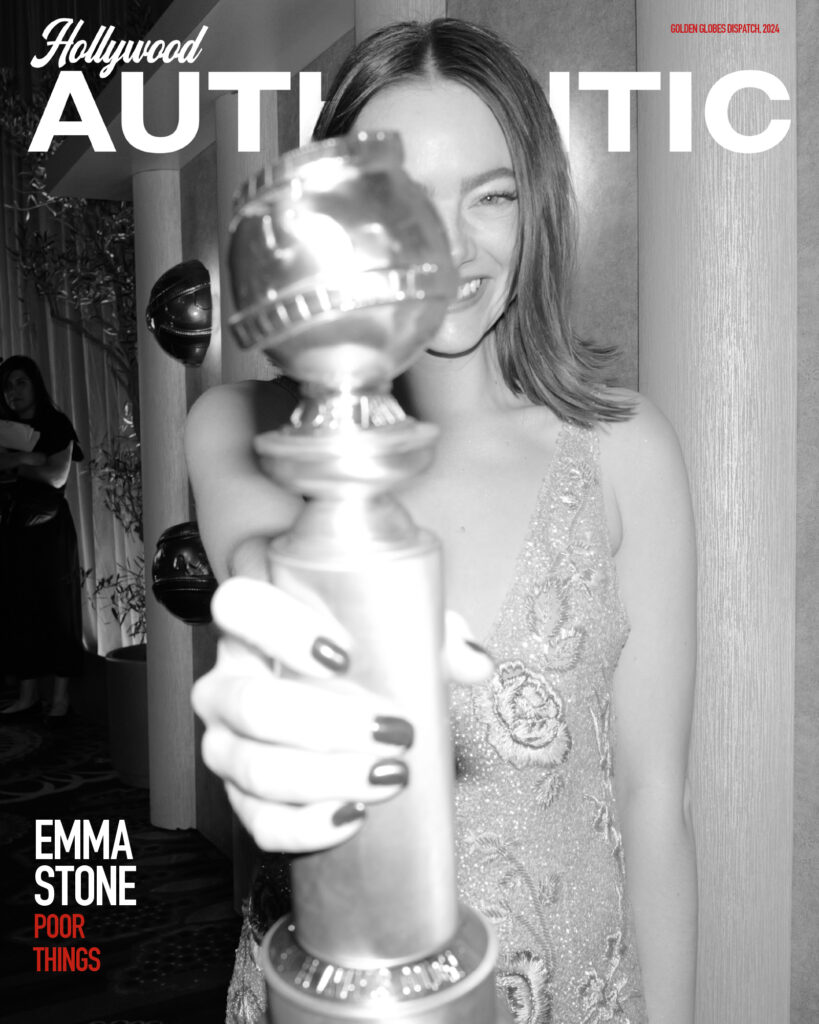

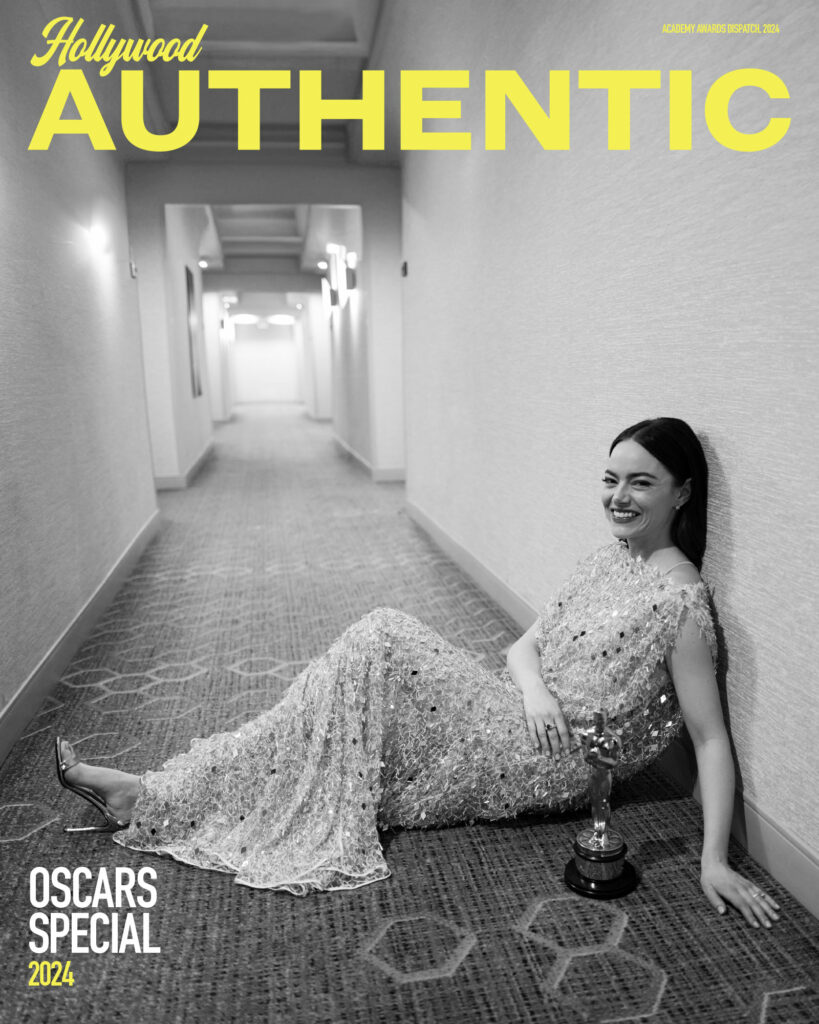

Da’Vine Joy Randolph was welcomed into the Best Supporting Actress community with Lupita Nyong’o, Jamie Leigh Curtis, Regina King, Mary Steenburgen and Rita Moreno championing each nominee in her category. Robert Downey Jr joined the best supporting actor club alongside Ke Huy Quan, Sam Rockwell, Tim Robbins, Christoph Waltz and Mahershala Ali; while his Oppenheimer castmate Cillian Murphy became a Best Actor winner with Forest Whitaker, Matthew McConaughey, Brendan Fraser, Nicolas Cage and Sir Ben Kingsley. Watching the show stage-side, the actors resembled Oscar statuettes as they stood together. The best actress category saw Emma Stone climb the podium to join Sally Field, Jessica Lange, Jennifer Lawrence, Michelle Yeoh and Charlize Theron.

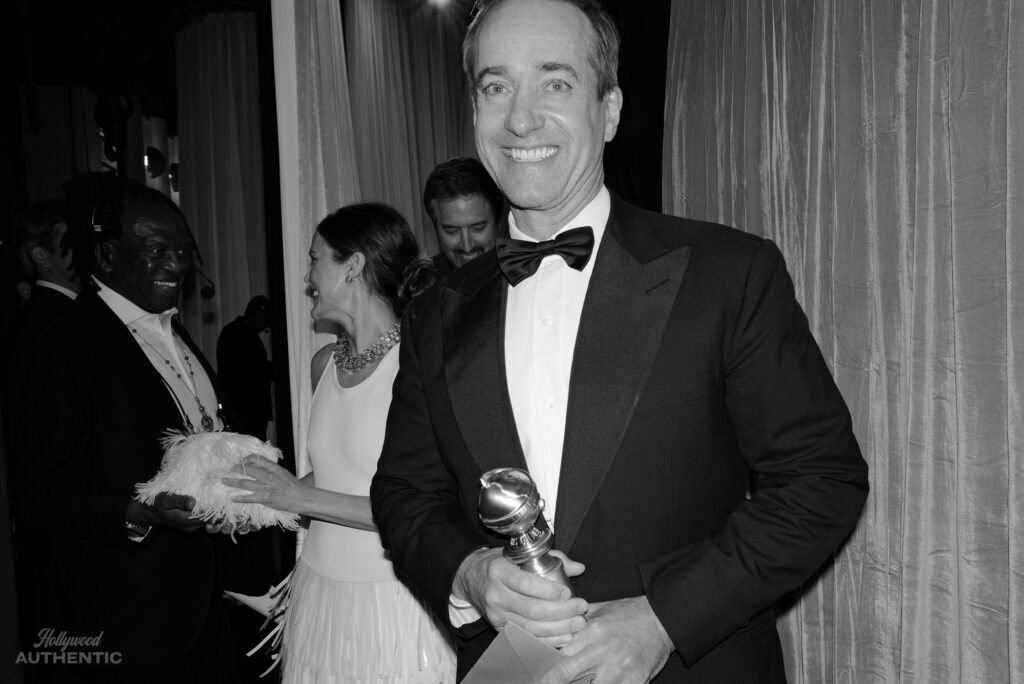

It was Stone’s second Best Actress award but the evening was notable for its firsts. Winning was a first for Robert Downey Jr (after three nominations), for Christopher Nolan as director, he and his producer wife Emma Thomas for Best Film, and for a British film to win Best International Film with Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone Of Interest. Matthew McConaughey waiting in the wings after Nolan’s win gave him a heartfelt congratulatory hug.

Family was also a theme of the night, especially as the date was Mothers’ Day in the UK. Bradley Cooper brought his Mom as his plus-one while Martin Scorsese attended with his daughter, Francesca. Best original screenplay winner Justine Triet in a sparkling Louis Vuitton suit noted her and her co-writer partner Arthur Harari juggled diapers and lockdown during their writing of Anatomy Of A Fall, Stone talked of her toddler daughter turning her life ‘technicolour’ and Nolan thanked his wife and producing partner Thomas – ‘producer of all our films and all of our children’.

Meanwhile, Sean Lennon, exec producer of best animated short, War Is Over, asked the audience to wish his mother, Yoko, a happy birthday and Mother’s Day. It was also a family affair for Billie Eilish, in houndstooth Chanel, and her songwriter brother Finneas O’Connell, whose performance of Barbie’s What Was I Made For? electrified the room and won the siblings their second Oscar for best original song.

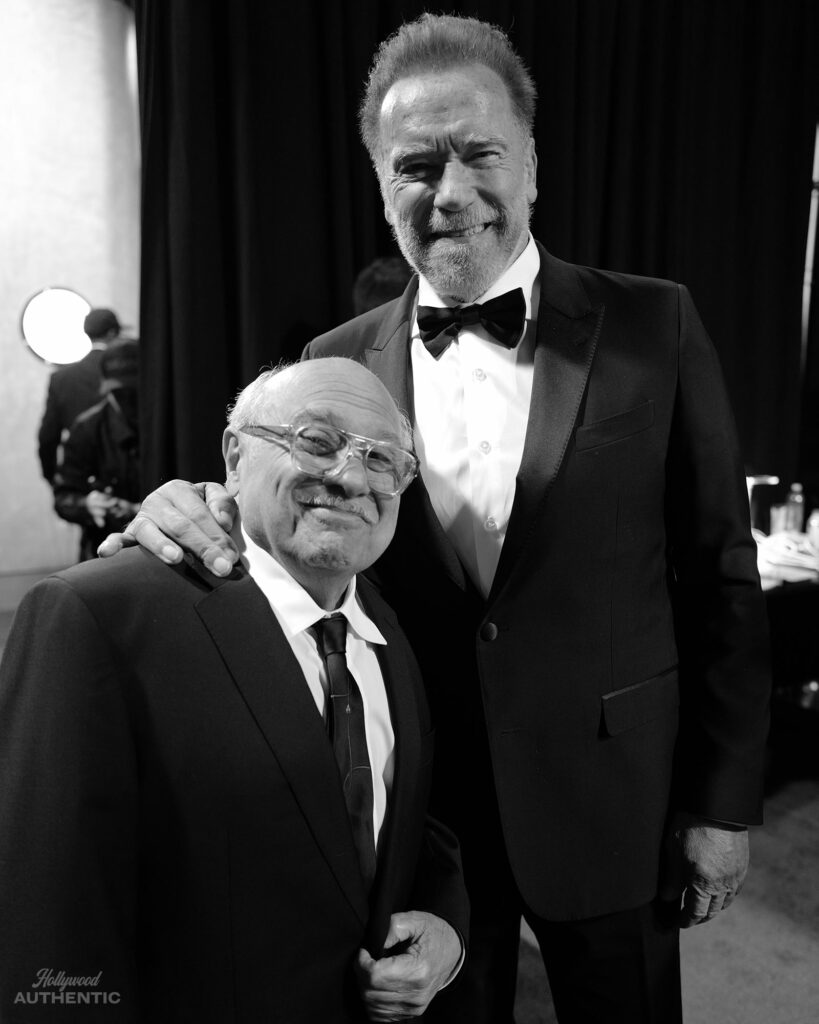

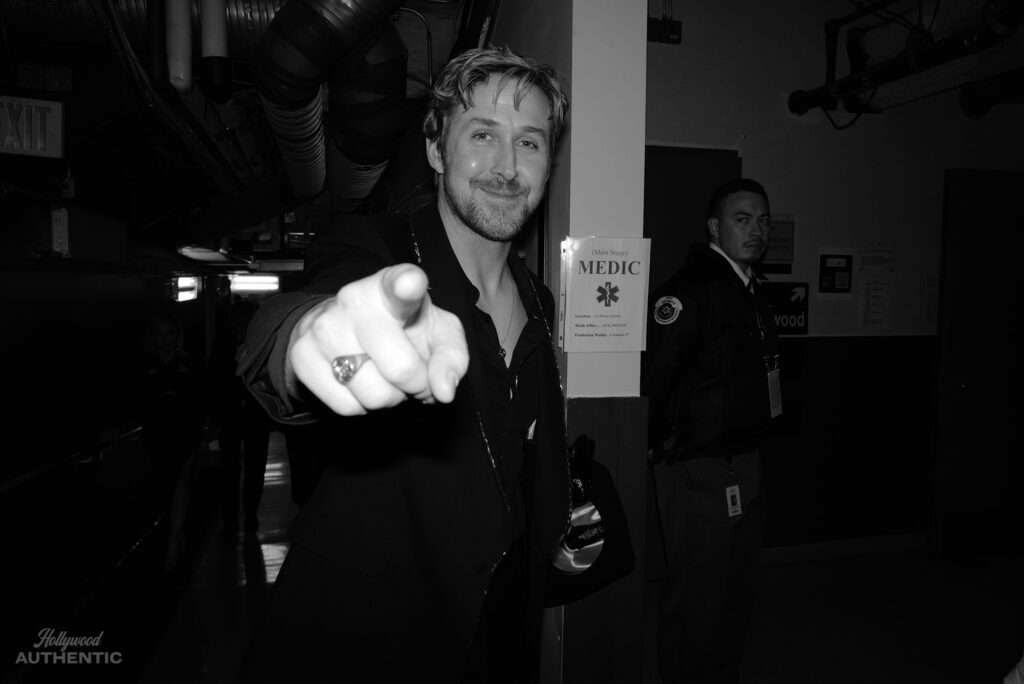

Their competition, Mark Ronson’s ‘I’m Just Ken’, may not have taken gold but Ryan Gosling’s full-throttle rendition of the song while wearing a custom pink Gucci suit involved the entire auditorium and featured many of the movie’s Kens, including Ncuti Gatwa and Kingsley Ben-Adir. It was a measure of the top-drawer nature of the show that Slash showed up to perform the guitar solo. It was one of many moments that demonstrated the star wattage wielded by the event – with iconic filmmakers and performers appearing together to remind movie fans of past classics or tease of future collaborations. Furiosa’s Chris Hemsworth and Anya Taylor Joy (in silver Dior); The Fall Guy’s Emily Blunt, shimmering in cream Schiaparelli, and Ryan Gosling; Beetlejuice 2 stars Michael Keaton and Catherine O’Hara; Twins co-stars Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito (both jested with Keaton over Batman) and Wicked’s Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo in character–appropriate gowns – Grande in pink Giambattista Valli and Erivo in structural green leather from Louis Vuitton. Zendaya, currently starring in the world’s number one movie, added further star power in Armani Prevé.

Nolan’s win felt all the more resonant for being handed out by multi-award nominated Steven Spielberg, who gamely played along with jokes by Kate McKinnon. But when it came to addressing world events, the show did not shy away. Jonathan Glazer made an impassioned speech about the Gaza/Israeli conflict, Cillian Murphy (in Versace) dedicated his award to ‘all the peacekeepers in the world’, Mstyslav Chernov, feature documentary winner for 20 Days In Mariupol, reduced the audience to silence with his speech about Ukraine. Host Jimmy Kimmel addressed US politics when he read out a social media review of the show by Donald Trump. “Isn’t it past your jail time?” he responded.

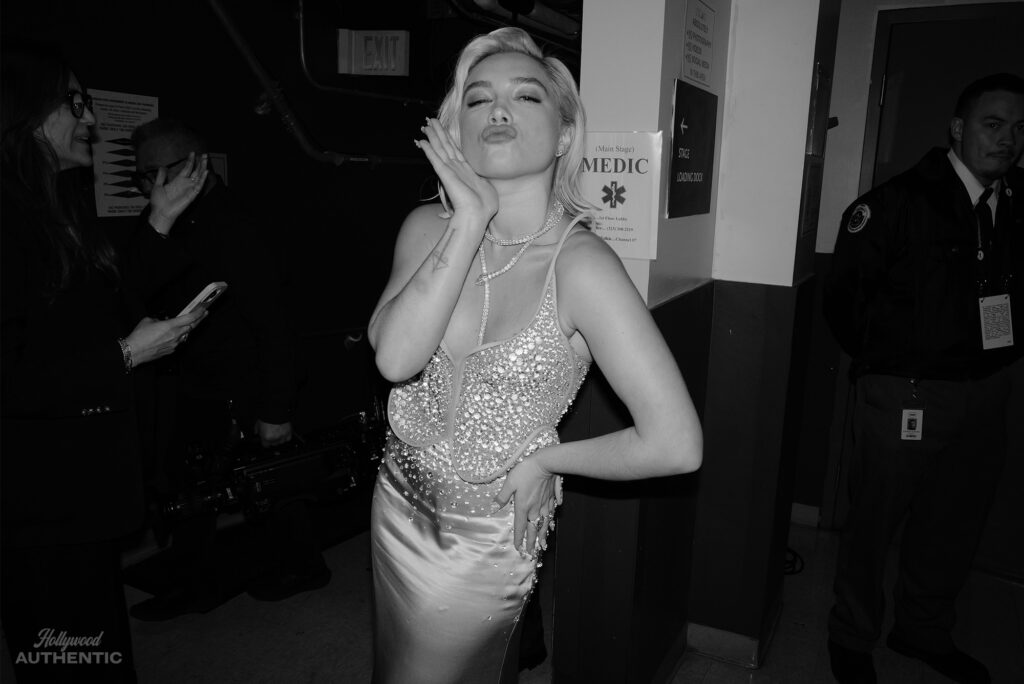

The night’s big win belonged to Oppenheimer presented by Al Pacino, with Emma Thomas confessing to having ‘dreamt of this moment for so long’ as she accepted Best Picture and praised the team surrounding her, including Florence Pugh in silver bejewelled Del Core. The cast and filmmakers hugged backstage, dazzled by the amount of gongs in hands.

An impressive, slick show that re-established the Academy’s dominance in awards season, presided over by four-time presenter and ultimate pro Kimmel, the 96th Oscars closed out as a true celebration of cinema and its stars – putting the difficulties of the past year firmly in the rear view window.

AWARDS

Best Film: Oppenheimer

Best Director: Christopher Nolan

Best Actress: Emma Stone

Best Actor: Cillian Murphy

Best Supporting Actress: Da’Vine Joy Randolph

Best Supporting Actor: Robert Downey Jr

Best International Feature Film: The Zone Of Interest

Best Animated short: War Is Over

Best Animated Film: The Boy And The Heron

Best Original Screenplay: Anatomy Of A Fall

Best adapted Screenplay: American Fiction

Best Makeup and hair styling: Poor Things

Best Production Design: Poor Things

Best Costumes: Poor Things

Best visual effects: Godzilla Minus 1

Best Film editing: Oppenheimer

Best documentary short: The Last Repair Shop

Best documentary film: 20 Days In Mariupol

Best cinematography: Oppenheimer

Best Live Action short: The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar

Best Sound: Zone Of Interest

Best original score: Oppenheimer

Best song: What Was I Made For?

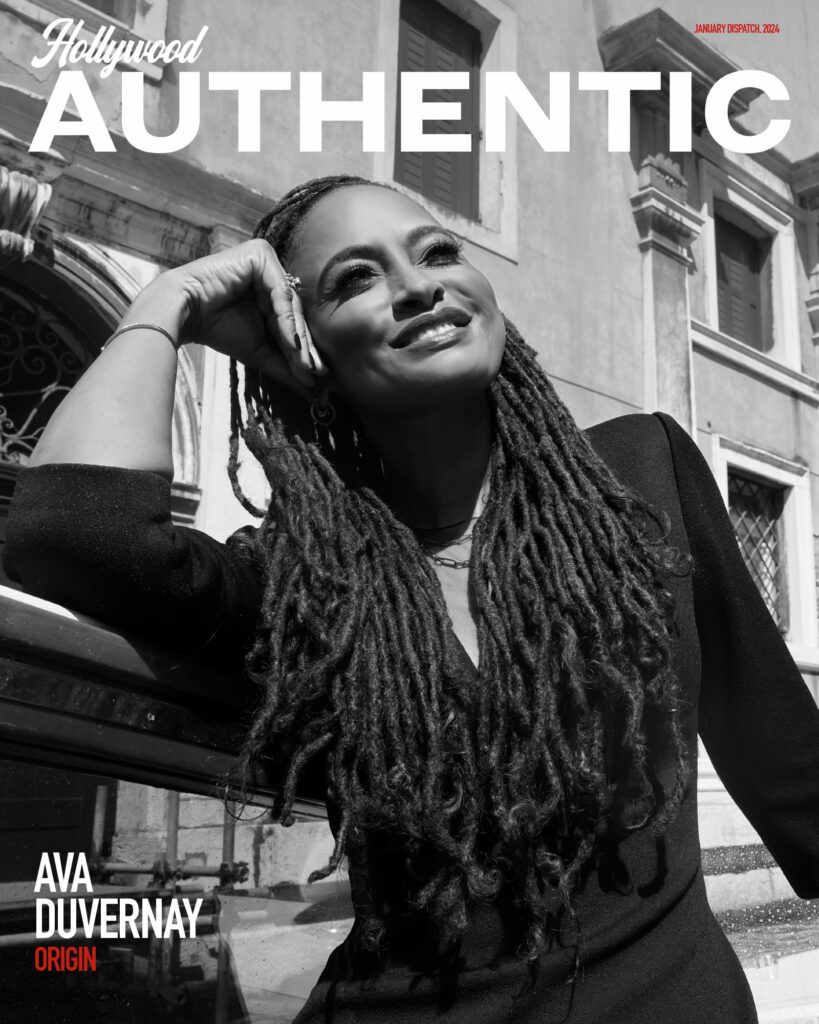

Words by Jane Crowther

Photographs by Greg Williams