Photographs and interview by GREG WILLIAMS

As told to Jane Crowther

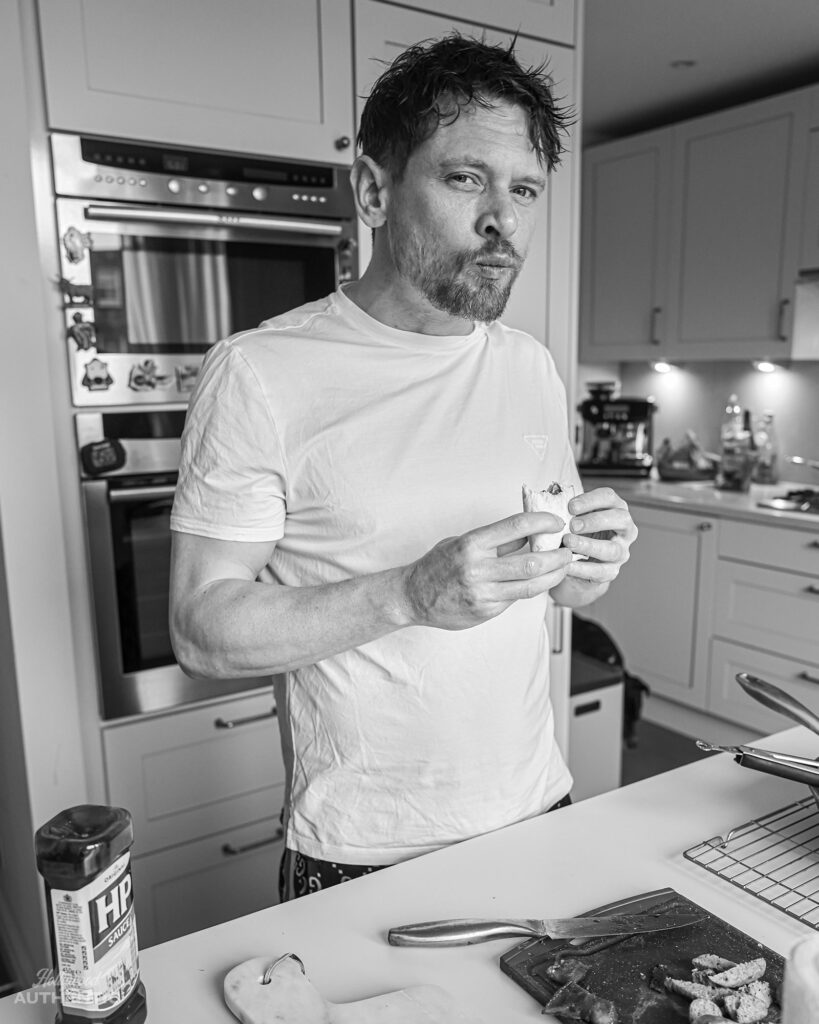

Jack O’Connell doesn’t like to hurry his eggs. ‘Low and slow,’ he insists, talking me through his breakfast wrap one drizzly March Friday morning in north east London when I meet him at his home. He takes half an hour to scramble his eggs as he crisps his accompanying black pudding, sausage and streaky bacon for our brunch. ‘I’ve always wanted to do a cookery show,’ he chuckles as he diligently stirs. ‘Don’t rush them…’

The actor’s domestic vibe is similarly exacting – ‘a tidy house, a tidy mind,’ he says of his spick ‘n’ span home – and is also reflected in the way he approaches his work. Though he has form playing troublemakers, rule-breakers and trailblazers in projects such as This Is England, Skins, Starred Up, Unbroken, The North Water, SAS Rogue Heroes and Ferrari, Jack doesn’t adhere to the idea of playing a hellraiser on and off screen. ‘It’s a funny one, isn’t it?’ he says, scarfing down his breakfast wrap. ‘If I’ve got a good head on my shoulders, and I’ve slept, and I’m rested, and I’m on set, it’s the best place to be. You know what I mean?’

As Bob the dog (more of whom later) weaves round our legs, Jack shows me round his house, pointing out the art he’s bought on his travels, including a Shane McGowan (‘I picked this up in Bantry, in Cork – it’s painted with peat from the bogs’), and the plants he’s currently cultivating. ‘This fella needs to cheer up,’ he says of one of the plants he’s just repotted, its leaves scattered around the floor next to it, ‘and this fella is thriving…’ His art is mainly of musicians, which is apt considering he’s next playing the husband of Amy Winehouse, Blake Fielder-Civil, in Sam Taylor-Johnson’s new biopic, Back to Black. ‘The last five or six years, I’ve started to really, really appreciate cinema. Not just actors, but the whole craft. I’ve always loved music but I never had the attention span for films as a kid. I’d get fucking bored – unless it was Braveheart with loads of scrapping, and all that action kicking off.’

While he might not have fully appreciated film and acting as a teen growing up in Derby, it intrigued him enough to attend a drama workshop twice a week in Nottingham with Ian Smith, the acting teacher who discovered Samantha Morton. It was while he was there that Shane Meadows came to cast for This Is England in 2004. He gave Jack his first role on a project that became an awards-winner and hugely influential to British cinema. ‘I was about 14 and suddenly I’ve got a BAFTA-winning film to my name,’ he marvels. Quite the trip for a kid from an industrial town in the north of England where working at the Rolls Royce or Bombardier plant was the usual ambition.

‘I just grew up there, playing football and doing all the normal stuff. My mum and dad worked every hour of the day. My mum had two jobs and still had bailiffs coming around. I remember the bailiffs coming and nabbing our TV. I was halfway through watching Pingu, and they fucking nabbed the TV. I remember my mum having to be really crafty with how she’d get food on the table and whatnot. And that was despite my dad working his arse off. He worked himself into the ground.’ The death of his dad at the age of 18 is something that still informs the 33-year-old today. ‘In terms of my relationship with him, I never got to speak to him as an adult, which is the biggest bereavement I still feel. With that kind of loss, you never get over it. You just cope. I had 18 years with a fine, fine man. I know lads that never even had a day with theirs. So it is what it is. But he got to see the start of where I was getting to with work.’

Shane Meadows has continued to be influential in Jack’s career as he recently turned his hand to directing a music video for Paul Weller. ‘I loved the shooting experience, then I got into the edit and was petrified, because suddenly I’ve got all this material, and I don’t know where it’s going, and I don’t know if it’s going to work. So I reached out to Shane; I hadn’t spoken to him in years. I told him what the score was, and he was like, “Oh, Jack, whenever I finish my gig, I feel like I’ve just won the award. And then I get into the edit, and I want to do myself in.” When you’re an actor, if it’s shit, you just blame the director. This time round, I had no one to blame, so it was on me.’

Jack’s latest acting work cast him opposite Marisa Abela as the two of them inhabit Amy Winehouse and Blake Fielder-Civil in Back to Black. Filming on location in the couple’s real-life stomping ground of Camden, Jack was reunited with Bob – a dog he’d befriended previously while acting in Cat On A Hot Tin Roof in the West End in 2018. As we head out to walk the dog, he tells me of their sliding doors moment. ‘I was shooting at the Dublin Castle pub in all my Blake garb. And who should walk past? It’d been about a year-and-a-half or two years. Bless him, he remembered.’ Now Jack borrows Bob for walks and hangouts from his owner, Lisa, when he has downtime between film shoots. Back to Black was a special project, he says, as we stroll the rain-slicked local streets to his favourite coffee shop. ‘I loved it, mate. Marisa was spellbinding. She threw everything at it. She was in every scene, it was heavy for her. I just really respected the work rate and the process.’ In preparation for the role, Jack met up with Blake, an experience he describes as something of a revelation. ‘His persona’s very public. He’s got plenty written about him in the tabloids. You think you’ve got the measure of someone based on what’s out there. I think he’s been vilified. And compared to the fella I met – I just got on with him. I was quite surprised.

Your best tools are your ears, and what you hear, and what you play off. You do a scene three or four times, and there’s gonna be a different nuance

It just felt like I had a lot in common with him. Any time he talked about Amy, it just rang true – and you can forgive being beguiled at that age. The kind of limelight that both of them ended up in… That meeting informed me a lot.’

As we arrive at Jack’s local coffee house I ask how he chooses his roles. ‘There’s jobs that you get, and there’s jobs that you chase, you know? It’s a bit of the law of attraction. There’s such a thing as just eating a bit of humble pie, and putting your hat in the ring. Even if you get fucking ignored, blanked and rejected, you know, not everything is just going to come your way. So I’m reaching out a lot more. I’m interested in being versatile.’ Before we can discuss further we’re welcomed warmly by Rodrigo, a barista from Naples, and we get chatting about football, Maradona and Paolo Sorrentino as Jack gets his coffee on the house. The two of them sing Napoli football songs together in Italian.

We move on to the local butchers, cups warming our hands, in search of a treat for Bob. As a proud northern working-class man, Jack recognises a certain pre-judgement operates in getting roles. ‘Do you think if I had a posh accent I would have a bigger career?’ he asks. ‘What I’m trying to understand – it’s bigger than myself, and my career – is that, do you get to have really good, aspirational jobs if you didn’t go to private school?’ Does he have a point? Though he’s played a wide range of roles, eras and accents with a diverse roster of helmers (including Michael Mann on Ferrari, Angelina Jolie on Unbroken, Jodie Foster on Money Monster), it’s interesting that there have been more American directors who have seen beyond his background. There are still ‘invisible lines and glass ceilings in play’ says the actor.

Jack has worked across TV, film and theatre – so which is his favourite space to get hooked on? ‘To use a cliché, film’s a director’s medium and TV is a producer’s. On TV you’re allowed more time to tell a story in a series, but you’re shooting fucking seven to eight pages in a day. Whereas, with film, obviously there’s always restraints as it relates to budget and what have you, but you can be a bit more focused. Your best tools are your ears, and what you hear, and what you play off. You do a scene three or four times, and there’s gonna be a different nuance to react to.’

His love of cinema is both as a practitioner and a punter, and as we stroll past his local picturehouse I ask him what role in any film he would have liked to have got stuck into. ‘The first one that’s coming to my head is American Psycho and Patrick Bateman. But I just think that what Christian Bale did with that is untouchable. And Jud in Kes. Sid in Sid and Nancy. That’d be the top three there.’ We nip into the retro cinema Jack describes as a ‘little viewing glass into yesteryear’ where he tells me over a Coke that he never watches his own work on a big screen alongside an audience. ‘I just watch at home, in the comfort of your own living room. So if you need to self-flagellate, you can just do it, in privacy! But there’s got to be a childlike curiosity to what you do. You know, when a toddler is playing, they’re not scared of how they’re looking, or if they’re getting it wrong. There’s a freedom to it. We lose it – the innocence, the fucking vigour, the fearlessness. To a toddler, fear doesn’t exist – the fear of getting it wrong; the fear of looking silly. But I think that’s got to be part of the process, isn’t it? You’ve got to be given room to fail. What’s borne out of that is what’s worth mining for. It’s the oxymoron of trying to be but not act. That’s always the goal. The best example I’ve got, which is lived in, is working with Shane Meadows. The cameras didn’t come out until the afternoon. He just spent the morning figuring it out. He didn’t know the story until he got into the edit. So we didn’t know. We were just there.’

Photographs, interview and video by GREG WILLIAMS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

Jack O’Connell can be seen in Back to Black, out now