Words & Interview by ARIANNE PHILLIPS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

The award-winning British costume designer who regularly reteams with the cream of directors tells Arianne Phillips about starting out with Lindsay Kemp, continuing to learn on the job and her signature personal style.

Sandy Powell is one of our most accomplished and celebrated filmmakers in the field of costume design – an incredibly prolific and visionary artist. She has well over 50 feature films to her credit. Sandy has designed some of the most groundbreaking, influential, enduring, visually stunning and iconic films of our time, some of which include Caravaggio, Orlando, The Crying Game, Interview with the Vampire, Michael Collins, The Wings of the Dove, Velvet Goldmine, The End of the Affair, Far from Heaven, Gangs of New York, The Aviator, The Wolf of Wall Street, Cinderella, Carol, The Favourite, Mary Poppins Returns, Living and The Irishman. Her esteemed list of directors she has collaborated with reads like a who’s who of some of our greatest and most important filmmakers, among them Derek Jarman, Julie Taymor, Sally Potter, Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Todd Haynes, Mike Figgis, Rob Marshall, Yorgos Lanthimos, and perhaps the greatest of his generation, Martin Scorsese.

Sandy started out as a student at Saint Martin’s School of Art and the Central School of Art in London where she specialised in theatre design, after which she started working alongside the great multidisciplinary artist, Lindsay Kemp. She has rightfully been acknowledged and awarded for her prolific and visionary work. The most notable is that she’s been nominated 15 times for an Academy Award, for which she has won three – for Shakespeare in Love, The Aviator and The Young Victoria. She has been nominated 16 times for a BAFTA award and won four, the fourth being in 2023 when she was awarded the prestigious BAFTA Academy Fellowship Award. Sandy was awarded an OBE in 2011 and has recently been promoted to a CBE. In 2013, she was made a Royal Designer for Industry by the Royal Society of Arts and, in October 2024, Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) presented ‘Dressing the Part: Costume Design for Film’ a comprehensive exhibition of 70 costumes from nearly 30 of Sandy’s films, spanning her 40-year illustrious career.

AP: At what point did you know that you wanted to pursue costume design? What was your entry path?

SP: That didn’t actually happen until I was in my teens, but from as young as I can remember, I was interested in clothes. I made dolls’ clothes. And then really quite early on, I attempted to make myself something. I think before I even knew how to sew, I cut up a skirt of my mother’s to try to make a pair of shorts. I was about four or five. There was a little girl who lived down the road from me and she had this amazing outfit that her parents bought her from Carnaby Street, psychedelic patterned little shorts, but with a tunic dress over the top. I was desperate for one of those. So I tried to make my own. I then got my mum to teach me how to make clothes, so I grew up choosing fabrics, and looking through the pattern books, and I used to make my own fashion magazines as well.

AP: I learned about choreographer Lindsay Kemp because of my own fascination as a teenager with David Bowie. So how did you connect with him?

SP: Like you, I read everything printed about David Bowie, so I learned about this amazing-looking man [Kemp]. And then I think I was 16 or 17 at school and I saw his company perform Flowers at the Roundhouse Theatre at Chalk Farm – it was like nothing I’d ever seen or experienced before. It was just the most magical, intoxicating event. But it wasn’t until a few years later when I was at Central School of Art doing a Theatre Design course that I got to meet him in person. At the end of my second year, Lindsay Kemp was doing dance classes at the Pineapple Dance Centre in Covent Garden. So I took myself off, and did a dance class and at the end, I went up and said, ‘I saw you when I was 16. I love your work. Do you want to have a look at some of mine?’ He said, ‘Yeah. Let’s go to the pub.’ And that was it. By the end of the summer, I was jumping on a plane, and went to Barcelona where he was living at the time to stay with him. He just said, ‘Oh, come and work for me.’ I then went home, spoke to my parents, called my college, and said, ‘I’m having a year out before the final year.’ I never went back. We stayed close friends until he died in 2019. He continued to be inspiring, amazing and funny.

AP: Then your first film was Caravaggio with Derek Jarman. How did you connect with him?

SP: I did the same thing as I did with Lindsay, really. I cold-called him. I was working in fringe theatre in the early ’80s, designing the sets and the costumes. I realised I was more interested in the costumes than the sets. I’d seen a couple of Derek’s films and I thought, ‘He’d be an interesting person to work with.’ A male friend of mine said, ‘Oh, I see Derek quite often in Heaven [nightclub]. I’ll get his phone number for you.’ So I basically got his phone number, called him up, and said, ‘Look, I’ve got a show on at the ICA. Would you like to come and see it?’ He came to see the show I’d done, and invited me back to tea. And that was the start of that relationship. Again – luck. What’s interesting about both of those people was that they were both incredibly generous with their knowledge, and surrounded themselves with young people who they then gave loads of trust to. I think that’s an incredibly generous thing to do, to give everybody their first chance. It’s amazing.

AP: Tell me about your experience of working on Caravaggio?

SP: I was thrown in the deep end. I was making the costumes with my assistant, Annie Symons, who’s now a costume designer as well. Honestly, we were two weeks of production before either one of us should be on set while they’re shooting! We were filming in this massive warehouse in Limehouse. We had no idea that that’s what you had to do. But, you know, we learned!

AP: You also worked with Sally Potter on Orlando…

SP: By the time I did Orlando, I’d already done a few more films with Tilda [Swinton] and Derek. Back in the early days, I’d do anything for the experience and for the job. One of my college tutors said, ‘When you’re starting out, you say yes to everything, because whatever it is, you’re going to learn something. It’s going to be a valuable experience.’ Looking back on it, I think we were so lucky then, because it felt like there were so many more interesting things to do, and people taking risks, as there was more money put into the lower-budget end of things, both in theatre and in film. What attracts me to a project now – is the script and the director. I usually now say it’s got to be a film that I would pay money to go and see. A film that I would want to see is a film that I would like to work on.

AP: The thing that struck me about your CV is these repeat relationships. There are multiple films with Todd Haynes, Martin Scorsese, Julie Taymor, Neil Jordan, Derek Jarman and Mike Figgis. What do you attribute to these enduring relationships and collaborations?

SP: You have to get on as human beings, as people. You have to like each other. With the director you have to work creatively well together. At the end, it comes down to respect and trust. And probably the most important thing is communication. And if you crack that, then you’re there – you’re halfway there. So I guess the relationships that endure are the ones where it works out, really.

AP: What did that feel like to see your career represented by the SCAD exhibition?

SP: It was like seeing your life flash before you. I suddenly thought: it’s 40 years of my life. But not only the work. You just remember what was going on in your life. And that was really quite emotional. So that was a career highlight. And most of the costumes in the exhibition were mine. I’d actually been collecting them, over the years. Because as you know, at the end of films, it’s really sad when you have to say goodbye to everything. And then, quite often, they just disappear. They get sold. They get packed up in boxes and left in some warehouse somewhere. And then years later, everyone forgets where they are, or what’s in that box. It’s not in my contract to keep costumes but a couple of times, there’s been an actor who has it in their contract they can keep the costumes, and then they give them to me, which is great. Or if there are doubles or multiples made, I ask if I can take one. And I’m glad I’ve taken care of them, so they now have a new life.

AP: Can you think of any particular experiences on any of your film projects that are career highlights for you?

SP: Obviously Caravaggio as the first one. Orlando as well, but then I might jump to Velvet Goldmine with Todd, which was an amazing experience. Another good one – Gangs of New York. I think probably it’s one of the highlights simply because, obviously, it’s my first film with Marty. But it was epic. It was extraordinary. It got bigger and bigger and bigger. And we shot the whole thing at Cinecittà, so I got to live in Rome for almost a year. Marty said that he wanted world in the Five Points to be a sort of world of its own. He gave me that freedom to come up with things… he responds very well. He’s very, very visual. He’s also amazing with providing reference. Back in the day, you’d get a box full of VHS [tapes]. For Gangs, I had to watch an entire film to look for a stripe on a collar.

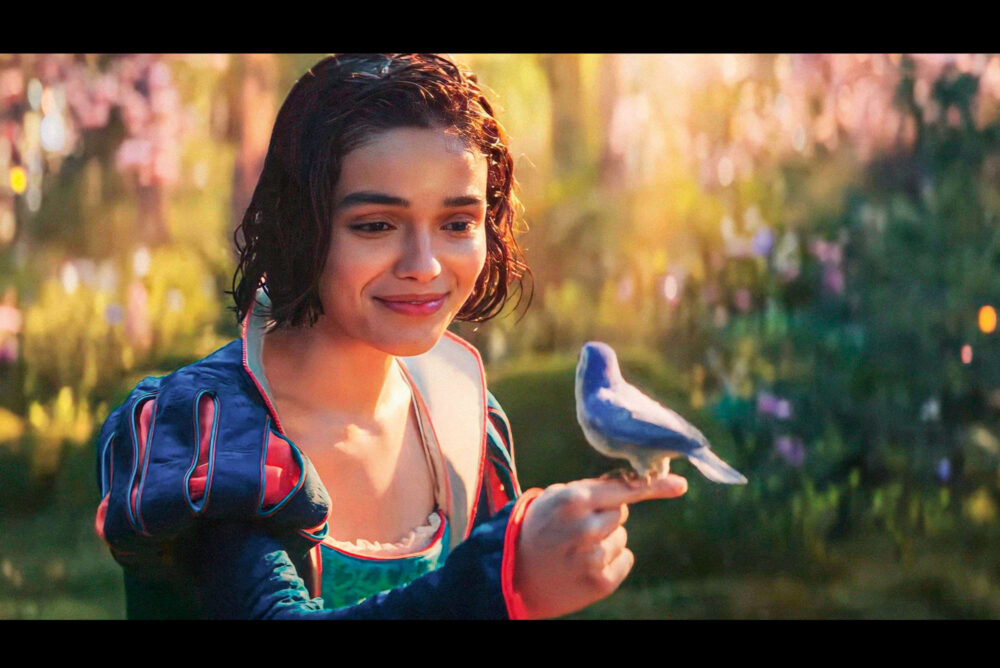

Then there was Cinderella. I really enjoyed doing Cate [Blanchett] for that, as the stepmother. Cinderella’s blue ballgown haunts me because every young person in the world loves that dress more than anything else! It didn’t occur to me when I started that I would be doing anything like the original, animated version. I went through many different colours and what I ended up with was a mix of different colours making up a blue that worked on Lily [James]. But then afterwards I realised that maybe if I’d done – I don’t know – an emerald green dress, somebody from Disney probably would have had something to say about it! But I didn’t remember there being a directive. I guess Carol is the other big one.

AP: What have you just wrapped on?

SP: That’s a film called The Bitter End, and it’s about Wallis Simpson in her older years, after the death of her husband, the Duke of Windsor. He passed away in 1972, and this film goes from 1973 to about 1980. Wallis Simpson is played by Joan Collins, and then the other protagonist in it, is a lawyer called Maître Blum, who’s played by Isabella Rossellini, who’s very thrilled to be playing her first baddie ever in her entire career! Obviously that was the main attraction of doing a film like this. The two main characters are two older females. How often does that happen? And The Bride is a wild, wild ride! It’s a film written and directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal, starring Jessie Buckley and Christian Bale. And it’s a very loose take on the Bride of Frankenstein story set in the 1930s. It’s out there. That script read like somebody taking a lot of risks. I guess it could be described as a punky, 1930s world.

AP: What advice would you give students who want to pursue this career?

SP: I think it’s: be prepared to work hard. Unfortunately, a lot of younger people now expect things to happen a lot quicker. They expect success or notoriety or whatever or fame to happen a lot quicker, simply because of social media. This is different. This is hard graft. It’s work. Be prepared to do the work, and to put the hours in at the beginning. I also think you should learn to sew. As a designer, I think you’ve got to learn the basics of making clothes. Obviously you don’t have to be the best in the world. But I really think you should understand construction. Doing a nice drawing means absolutely nothing if you don’t know how to specifically communicate that, if you don’t know how the costume is put together. To actually understand what isn’t working in a fitting – this only works if you know how things are put together. It helps if you understand what your cutter is talking about, or wanting to do to make something work. You’ve got to have the basic skills.

AP: You’re known for your personal style – is that an important part of being a costume designer?

SP: I’ve always enjoyed dressing up; I’ve been a show-off in that sense, I suppose. I’ve enjoyed expressing myself through clothing. I also think that as a costume designer, the first thing you have to do when you meet an actor is getting their trust. And I think if you look OK yourself, you’re a little bit of the way there. I like to think that that gives somebody confidence in me.

AP: Is there a person or a genre you haven’t worked with yet that you would really love to?

SP: No. I’m not interested in spacesuits at all. Or creatures or Hobbits or superhero outfits. Other people are much, much better at that. I just like doing more of the same. You still continue to learn something new every time you do a job, even if it’s a period you’ve done five times before.

Words& Interview by ARIANNE PHILLIPS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

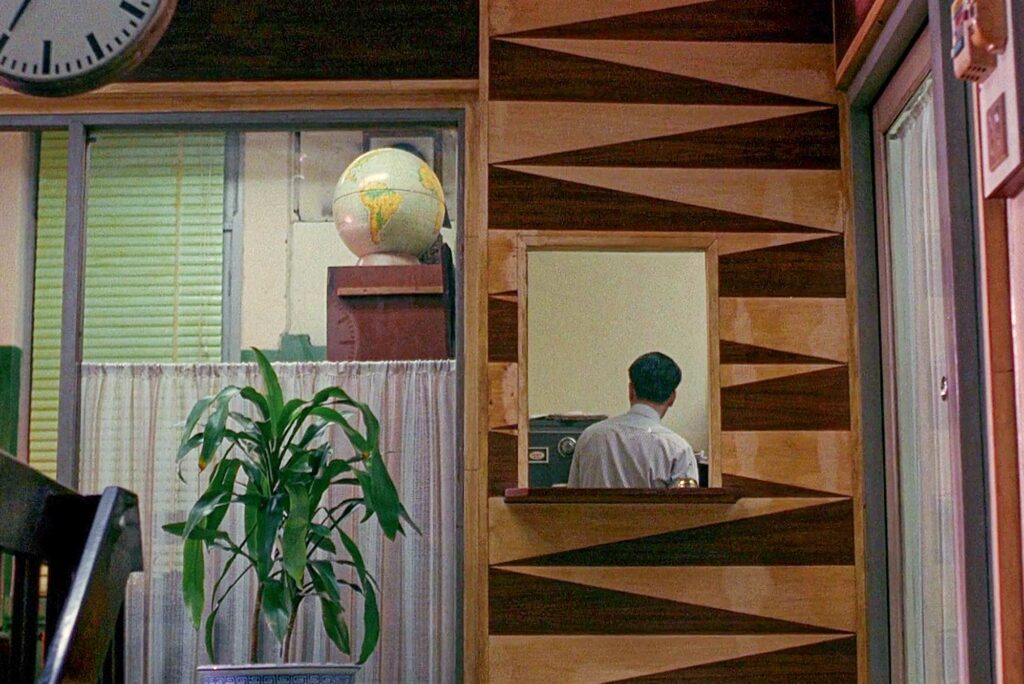

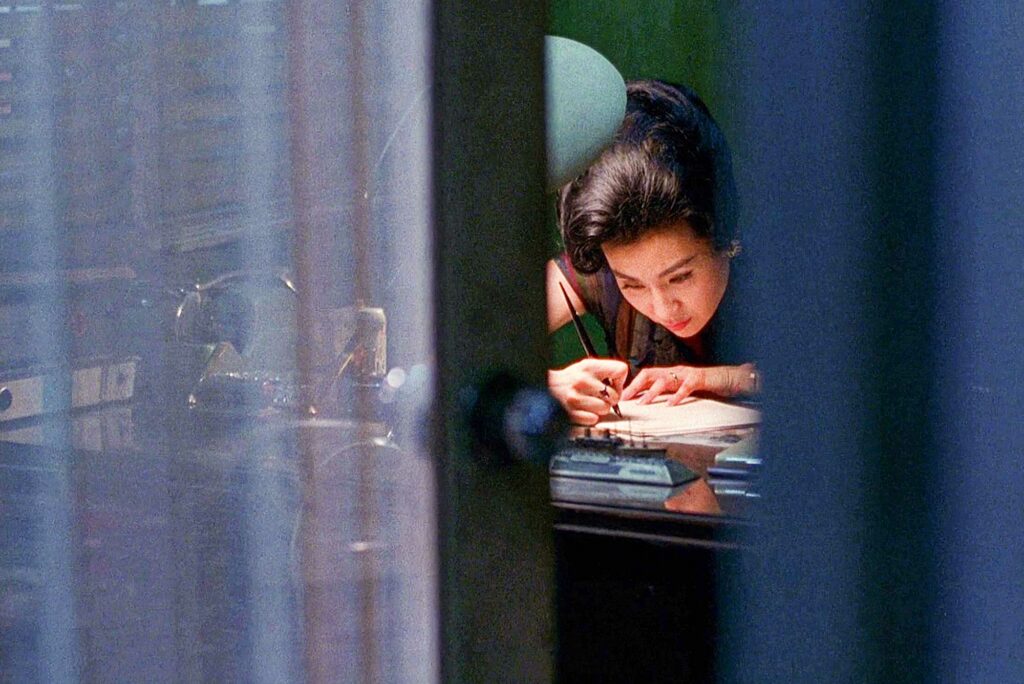

Carol / Caravaggio / Far from Heaven / Gangs of New York / Orlando / Snow White / Velvet Goldmine