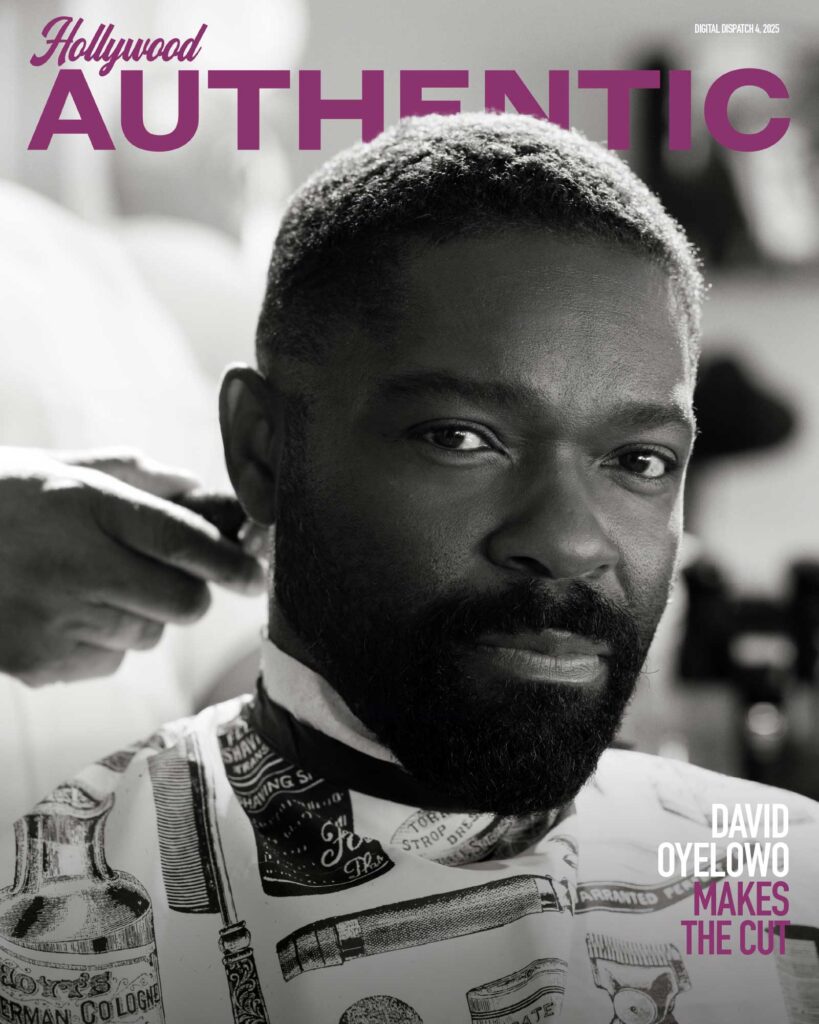

Words & Interview by ARIANNE PHILLIPS

The trailblazing, award-winning costume designer, who has worked with filmmakers from Spike Lee and John Singleton to Ava DuVernay and Ryan Coogler, tells Arianne Phillips about being a ‘first’ in Oscar history and how community has shaped her career.

Ruth E. Carter is a costume designer extraordinaire and her body of work speaks for itself. She has designed costumes for beloved and game-changing films such as Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, Amistad, How Stella Got Her Groove Back, What’s Love Got to Do with It?, Selma, Dolemite Is My Name, Coming 2 America 2, Black Panther and Wakanda Forever. She’s been nominated four times for an Academy Award, of which she won twice – making history as the first African-American costume designer to win an Oscar, as well as the first African-American woman to win multiple Oscars in any given category. In 2019, she received the Costume Designer Guild’s career achievement award and is the second costume designer to ever have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (after Edith Head). Not only a prolific artist, she’s also a leader in the costume community, serving as a governor of the costume designers’ branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Her book, The Art of Ruth Carter, was published in 2023 and her latest project, Sinners, is currently in cinemas.

AP: Let’s talk a little bit about your origin story. Where did you grow up, and what brought you to costume design?

RC: I grew up in Massachusetts in a little town called Springfield, the home of the Basketball Hall of Fame. My mother was a psychologist for the city – and I say that because my mom was the first person who actually taught me how to see people, and see the stories behind the people. I had two brothers who were visual artists – my brother who’s closest to me in age really loved to sketch. He loved pencil and graphite. We would sketch faces. We had a little mouse that we drew. He wore a tam [hat], and had the Black Power fist up all the time. It was fun! My oldest brother, Robert, did fine painting, oils and portraits. We all looked up to him. So my family was artistic but I tried to divert away from it when I went to college and majored in education. I decided to change my major to theatre arts, and very soon was known on campus as the costume designer. My main focus was to get theatre projects done, whether it was the music department doing a musical, or a fraternity doing some special step show, or Black theatre. They weren’t teaching costume design in the theatre department at the time. I went into a little costume shop that was in the theatre department. It was uninhabited. No one was using it. But when I opened up that door, it became my learning lab.

AP: I relate to that as a theatre kid. In your career you’ve really touched on every genre from historical pieces to biopics to comedies. What informs your choices?

RC: I would love to be the person who chooses, who goes out into the backyard to my film tree, and I pick: ‘Oh, I love this one, and then I love that one.’ But I feel like I have a certain reputation, and the films that are being offered to me, they’re in my wheelhouse. It doesn’t mean that you’re typecast, just that people think that this is something that you would be inspired to do. I’m always given the challenge. I’d love to do something one day with one person in it – you know, Krapp’s Last Tape. But I get the ones with the armies and the battles, with a cast of hundreds. I’ve been really fortunate to have offers that are really juicy, that are interesting and challenging. And that’s what I look for. I really love when I admire the filmmaker, but I also love to support young filmmakers that have promise, and I really want a good experience – for them to learn as well. When I first met Ryan [Coogler] at Marvel, I sat across a young filmmaker that admired Spike Lee, and told me that he was happy that I came in to interview. He admired my work as a student of film. So when that happens, it charges you up, and you go, ‘I am going to do the best I can for this young filmmaker, because it’s really about being part of a film family, and really liking the person you’re working for.’

AP: You created a travelling exhibition – Afrofuturism in Costume Design – your book also touched on this. I wondered if you could just illuminate a little for our audience about your relationship to Afrofuturism?

RC: I feel that my whole career has encapsulated Afrofuture. What we know of Afrofuture is taking culture and infusing it with technology, and presenting it in a way that, you know… What would things be like without colonisation? How would this technology have been advanced by these different cultures? I take Afrofuturism a step further. When I’m on the set with Spike Lee and he’s envisioning the story of Do the Right Thing, he is bringing in prose and political statements. He’s creating a protest film. I feel that Spike is embodying his own Afrofuturism, his view of a better tomorrow where we see ourselves on screen in a way that is much more realistic to what we know, and how we see our community, and how we know beauty. It’s retraining the eye, not only to see costumes in a new lens, or through beauty, but also to retrain the eye to see beauty standards differently. I think that those kinds of edicts are the things that I grew in this industry to embody and embrace, because I had a mission. I had a responsibility to that, because I was blazing a trail for the future costume designers who looked like me, and I wanted them to feel not pigeonholed or in a box to do things a certain way. When we crafted Mo’ Better Blues, we showed Denzel Washington and Wesley Snipes on stage in the jazz club. These were the images that we weren’t seeing in cinema. Also, Ava DuVernay on the set of Selma, directing. You know, we’re not only teaching through the medium of film and storytelling – we’re also teaching by example. Now our community could see a woman directing. Or a story being told about your neighbourhood. That, for me, is Afrofuture. That’s how you groom the Afrofuture for yourself and for your community.

AP: You designed films with Spike Lee and John Singleton…

RC: I met John Singleton at a panel where Spike was speaking. It was such a tight, little network in the ’90s that you might be out partying with John Singleton, having never worked with him, but we were a little film tribe.

AP: I think that one of the attractive aspects for me as a young person coming into filmmaking was the collaborative, communal idea. As artists, when we have a director, or even an actor, with the same vision and purpose, we can really be creative.

RC: And sometimes it’s just about helping them find the creativity. A lot of times, our actors will come to us from another set with very little prep, and you’ve been on it for weeks, just delving into research, and you’ve collected all kinds of things that you’re excited to show them and share with them. I’ve had someone like Forest Whitaker ask to see more of my research so that he could spend some time with it in his hotel. When they are like that, you know that they are committed to creating a great character.

AP: I’ve had that happen when they come into the fitting room, and they say, ‘Thank you. I didn’t know who I was.’ A director that I’ve worked with says that the fitting room is the most important because it’s the portal into the film. And oftentimes we’re talking to an actor, or maybe a day player, that hasn’t even got to set to sit down with the director.

RC: I’ve had an actor say his first sitting is his first rehearsal. It’s really beautiful.

AP: Can you talk a little bit about biographies versus dramas? And the challenges of dressing historical figures?

RC: Fortunately, with someone like Malcolm X, there were quite a few photographs of him, but not enough of him as he was a young boy in the dance hall years, and all of the years where he hustled in New York City. It becomes a relationship you have with the character or the person, gathering what you can see of them, and also imagining during the times what they would be challenged with. No one’s life that we portray in biopics is exactly the way that it was in their real life, even though we attempt to get as close as we can, because we only have two hours to tell their whole life. And we have to make it cinematic, and make you feel empathy, and make you cry, and make you laugh. I research a lot and that tells you things that you wouldn’t know. Like they built stoves in Detroit, so that informs ageing of the costumes – that these people who are workers coming down the street to eat, or were coming home, they could have worked at the furnace supply factory.

AP: Do you have any career highlights that stand out for you?

RC: First, I have to say that those years in the ’90s, bouncing back and forth between LA and New York every year, going to New York to work with Spike, and then coming back to California to work with Robert Townsend and Keenen Ivory Wayans – I really got both sides of the coin. I was able to do comedies like I’m Gonna Git You Sucka and B*A*P*S and understand their perspective – and then to go back and work with Spike on something rich like Do the Right Thing and Mo’ Better Blues and Crooklyn and Clockers. Really just the experience of both the East Coast and the West Coast in that way, every year for 14 years, was an incredible experience for me. But I would say that the one experience that stands out the most is being in Egypt, shooting Malcom X’s hajj to Mecca, having built the hajj in the desert, because we couldn’t go into the Holy City and shoot there. We rebuilt it. Our first day of shooting, we were shooting at the pyramids, and we left the hotel – it was still dark out – because we wanted to shoot a priest singing the morning prayer at the pyramids. I’m standing in the desert with Denzel Washington, on a Spike Lee joint, looking at the pyramids with a Muslim priest singing the prayer – it was so spiritual and so meaningful. It was an experience that you seldom see anymore, because movies will put a green screen around the whole set, and be in Egypt. But we were actually there.

AP: In terms of being the first Black woman to win an Oscar, and the second time in the same category – how does that resonate for you, not only in your accomplishment but in general?

RC: In 1993 I was nominated for Malcolm X. I was the first Black woman to be nominated for costume design. I was like, ‘Wow.’ But then I thought, you know, ‘Wow, it’s 1993. In this day and age, we’re still examining firsts.’ So that told me that the film industry was not wide open. I was able to do something that could open a door. And so my accomplishment then formed what this is going to mean for the culture. As time went on, Amistad happened, and meeting Steven Spielberg, and working on set with Steven, was another highlight. And then I was nominated. It was the loneliest nomination ever because the film didn’t get the nomination. But I was reminded that this is not the reason you’re doing this; it isn’t the crux of what makes this experience so impactful and so important for you.

And then Black Panther happened. It was incredibly hard. It was really immersive. I look at pictures of myself, and I’m like, ‘Oof, there’s another bad hair day!’ But you had to give it your all. So to win for Black Panther, it was bigger than anything. To stand on that stage, and look out and see Spike sitting there, to see Chadwick Boseman, just smiling big and bright – it felt like I was still doing this for the culture; still achieving these goals for the community; still being an example for the next young girl coming in behind me, to show that they can, too. And that’s really what I was overwhelmed with joy about. And social media made it undeniable, because now you see the audience. You see what they want, and you’re able to actually give it to them, and talk about it. When the trailer for Black Panther dropped, I’m sitting at home, and I saw something come over my phone on Twitter. It was a question about the Himba tribe. I answered the question, and then it blew up.

AP: Can you tell us about Ryan Coogler’s latest film, Sinners, with Michael B Jordan – a departure for you because it’s a horror film?

RC: I had to get used to putting blood all over the costumes! We had to have things built in multiples because it was the 1920s, Mississippi Delta. And then, all of a sudden, here comes the vampires. It was a lot of fun. It was really wonderful to paint that landscape, to get that richness of time and place and people, and then depart from it, and have the fighting off of vampires, and stakes, and bites, and blood. Yeah, it got pretty messy [laughs].

AP: And now you are producing a film with Serena Williams…

RC: We are telling the story of Ann Lowe, who was a fashion designer. She was the first Black woman to have a shop on Madison Avenue. Her clientele were all of the high upper-class families in New York. She did a lot of debutantes, and Jackie Kennedy’s mom brought Jackie to Ann Lowe to have her wedding dress designed. When it was reported in the New York Times about Jackie Kennedy’s beautiful dress, she was listed as the ‘Negro Seamstress’. This was 1953. The Civil Rights Movement was just coming in. So to navigate these rich families, she had to kind of code switch. She had 35 people working for her. She wasn’t sewing on a sewing machine at home. She had a business. Her work is amazing, and it’s at the African American Museum in DC. It’s at the Met. People have collected her pieces in museums, but nobody knows, still, very much about her. So we are hellbent on giving her her flowers, and also showing how she was navigating the times, and how she was this genius of a woman who was doing all of these beautiful dresses.

AP: What advice would you give to a young person who wants to be a filmmaker?

RC: I think a young person who wants to become a costume designer, really needs to be committed to it. It’s a whole life experience when you’re doing costumes, and it’s not always glamorous. Come into this knowing that this is something that you really want to do, and you’re always going to be a student of it. The minute you think you know, then you’re only scratching the surface.

Words by RUTH E. CARTER/ARIANNE PHILLIPS

Do The Right Thing / Malcom X / Black Panther / Black Panther: Wakanda Forever / School Daze