Words by CHRIS LEADBEATER

Luca Guadagnino’s heady depiction of ’50s Mexico City in Queer is as seductive as the love affair at the heart of the tale. Hollywood Authentic celebrates a metropolis with a rich cinematic history and a spicy selection of attractions.

The last time we saw Daniel Craig on screen in Mexico City, he was striding across the rooftops along its main avenue. And death was lurking on the street below – in the form of gaudily coloured floats and giant cigar-chomping skeletons; a ‘Day of the Dead’ parade in full flow.

Death was on Craig’s mind as well, through the crosshairs of his rifle. As James Bond in Spectre, Craig sought men to kill. Fast forward a decade, and he is seeking men for thrills – in Luca Guadagnino’s opulent, delirious adaptation of William S Burroughs’ Queer, playing a thinly veiled cinematic version of the American writer and poet.

Part of the ‘Beat Generation’ of anarchic wordsmiths who helped to redefine the limits of literature in the mid-20th century, Burroughs wrote about his post-war ex-pat experiences in Mexico City, in a novella also titled Queer. Its pages were so crammed with content that would have been deemed shocking at the time that it went unpublished until 1985. This was a chaotic period in the writer’s life. Burroughs had fled the United States in 1949, in the wake of a drugs raid on his New Orleans home that had raised the prospect of jail time. Addicted to heroin, he tried to carve out a new life in Mexico City; bar-hopping, picking up lovers and ultimately, in September 1951, killing his wife, Joan Vollmer, during a riotous night at a friend’s apartment. He was, he said, attempting a ‘William Tell stunt’ of shooting a glass (rather than an apple) placed on top of her head – only to miss the target and hit his spouse. Whether this was (as he claimed) drunken high-jinks gone tragically wrong, or a pre-meditated act (he was convicted of manslaughter in absentia), remains a matter of debate. Burroughs made a run for it again before the case could come to trial, ultimately wandering the Ecuadorian Amazon (an ‘adventure-quest’ that the movie covers) in search of the psychedelic drug yagé (ayahuasca).

Guadagnino has been obsessed with the novel since reading it in his youth. In his vicarious hands, Burroughs’ tale of ‘William Lee’, a drink-addled romantic, comes vibrantly to grubby-gorgeous life, as Craig’s crumpled-linen barfly pursues a young naval veteran, Eugene Allerton (a barely disguised avatar of Burroughs’ lover Adelbert Marker), played by Drew Starkey. A viewer will no doubt want to head straight to the airport and Mexico City after the end titles, thirsty for mezcal, sultry temperatures, the Baroque architecture and the sound of mariachi bands. But Guadagnino’s sleight of hand is so subtle that you scarcely notice one particularly important fact: that everything was filmed either on Italian soundstages (at the iconic Cinecittà Studios in Rome), or in Ecuador, where the capital Quito offered a splendidly convincing impression of its Mexican counterpart.

This, itself, is quite the feat, because Mexico City is hard to impersonate. It ranks as the biggest city in North America (and the sixth biggest on the planet); a melting pot of 22 million people. And it is fascinating when caught on camera. Even if Guadagnino’s lens is dealing in misdirection, plenty of other directors have cast the city as a star attraction. Its credit list over the last three decades has been impressive. And diverse – sometimes showing the city as an affluent jewel; at others, scratching at base layers of dirt and crime.

Y tu mamá también (2001) – Alfonso Cuarón’s coming-of-age masterpiece – pitches the city as an enclave of monied insouciance; a place that bored teenagers Julio (Gael García Bernal) and Tenoch (Diego Luna) cannot wait to leave, on an impromptu road trip to the Oaxaca coast with an alluring older woman. Cuarón repeated this trick in Roma (2018), his Oscar-winning dissection of family life in the well-to-do titular neighbourhood. But here, the world beyond the driveway is darker. Set in 1971, the plot draws on ‘El Halconazo’, that year’s brutal massacre of student demonstrators by paramilitary group Los Halcones.

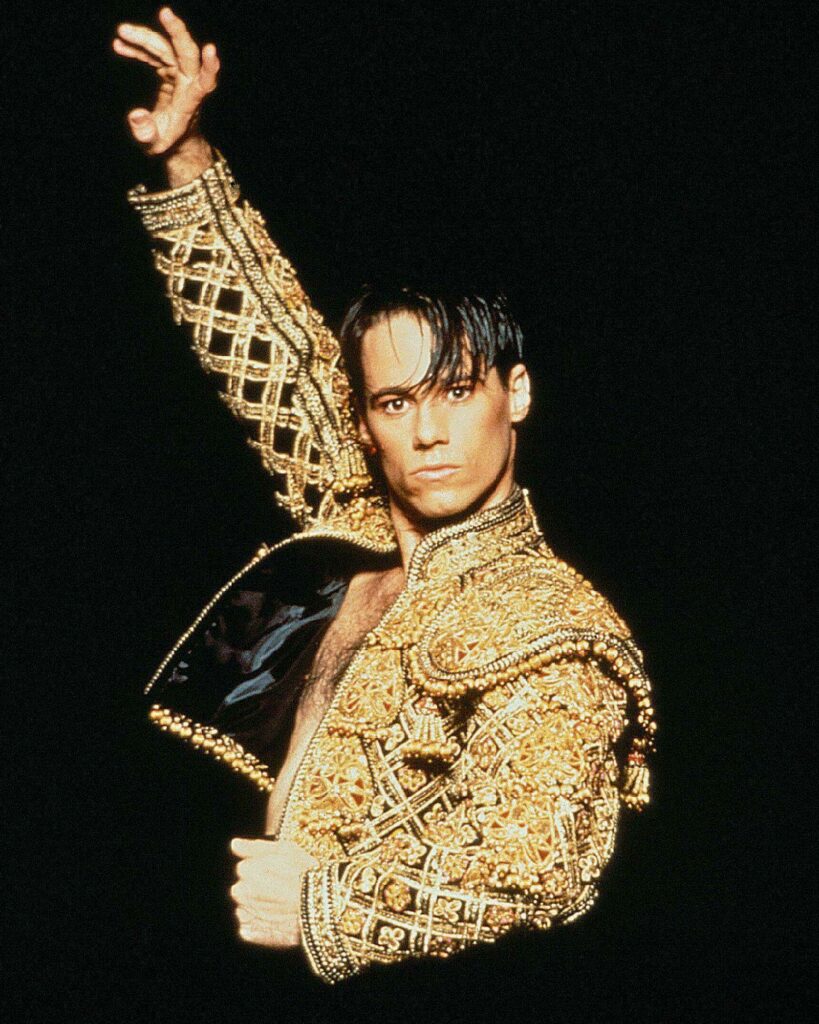

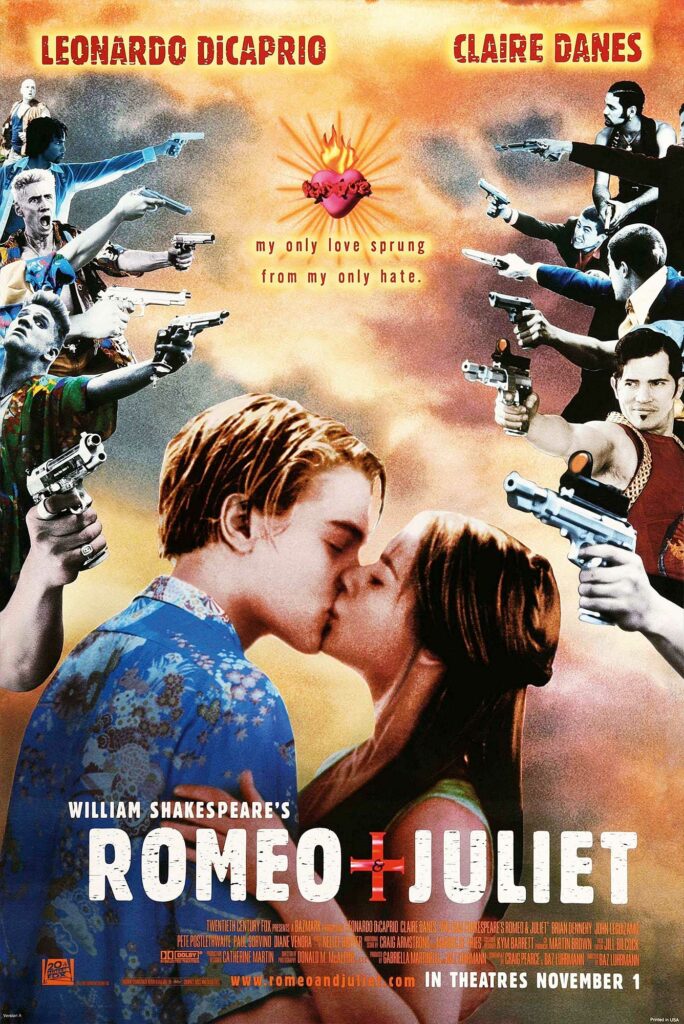

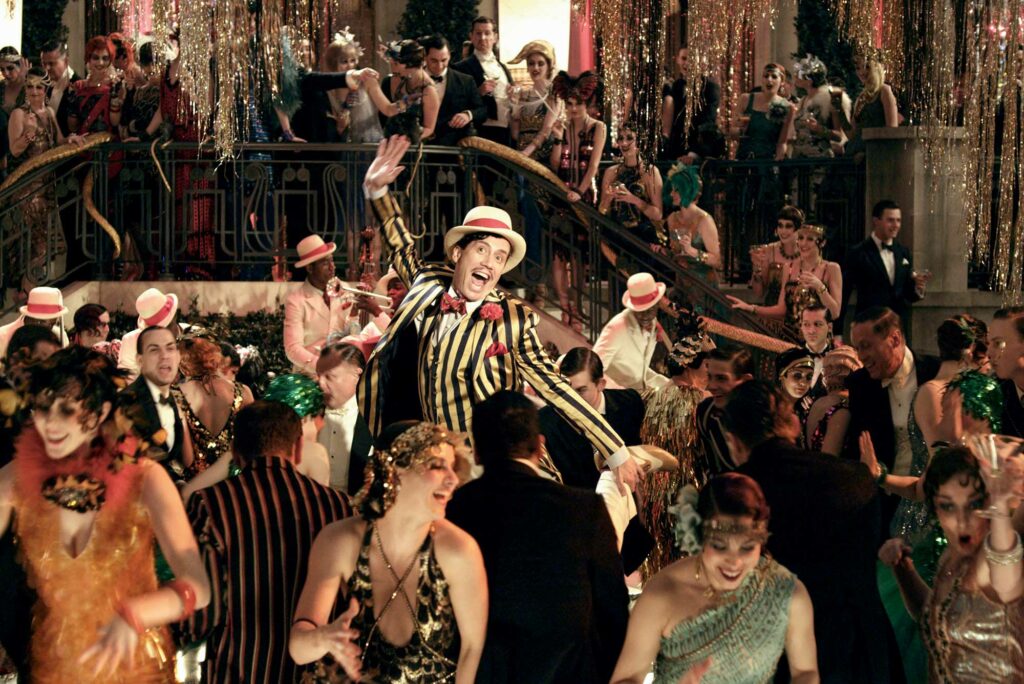

This bleaker seam was mined by Tony Scott in his 2004 thriller Man On Fire – sending Denzel Washington into Mexico City as an ex-CIA bodyguard tasked with the protection of a rich man’s daughter (scenes were filmed in the city’s Estudios Churubusco, as well as surrounding districts). And Baz Luhrmann opted for an on-edge Mexico City in his 1996 tour-de-force Romeo + Juliet, using it as one of the real-life settings for his fictional Verona Beach. The Capulet mansion where the lovers (Leonardo DiCaprio, Claire Danes) meet is the Chapultepec Castle, the former royal palace that, as of 1939, has been Mexico’s National Museum of History, perched on a hilltop that was sacred to the Aztecs.

The shadows are perhaps lengthiest in 2000’s Amores perros – the first chapter of the ‘Trilogy of Death’ directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu. Here, three seemingly distinct tales – of a barrio teen (Bernal), a model (Goya Toledo) and a hitman (Emilio Echevarría) – converge around a car crash. While several scenes were filmed in high-end neighbourhoods such as La Condesa and Lomas de Chapultepec, Iñárritu’s commitment to authenticity saw the tape roll in some of the city’s more deprived districts.

Such movies are a demonstration that, in a metropolis the size of Mexico City, there will always be light and shade; want colliding with wealth. But they are also evidence of the city’s strong directorial bloodline. Both born in its midst in the early 1960s, Cuarón and Iñárritu are just the latest visionaries to have emerged from the city’s fertile cultural soil. There have been many other ‘chilangos’ behind the camera – feted filmmakers Luis Estrada, Carlos Enrique Taboada and Juan Bustillo Oro, to name just three.

For all the occasional uncomfortable truths told by Cuarón and Iñárritu, Mexico City offers an upbeat (and safe) experience for visitors keen to embrace its charms – and a more immersive version of Mexico than that found on the beaches of Cabo or Cancun. Particularly amid the important sights of the Centro Historico – and in the more salubrious districts, where tourists are most likely to put down their luggage.

At root, the city is still Tenochtitlan, the pulse of the Aztec Empire, which was conquered by the Spanish crown in the first half of the 16th century. The main square, Zócalo, was also the centrepiece of the indigenous city, and its function remains unchanged. Its echoes are noisy, its past never invisible or inaudible. The National Palace, on its east side, is the seat of the Mexican government, but much of its masonry is a recycling of the palace of Moctezuma II, the Aztec emperor whose reign (1502-1520) coincided with the arrival of the conquistadors. Similarly, the Metropolitan Cathedral – a Gothic pile, constructed in stages between 1573 and 1813, which stands on the north flank of the plaza – is also hiding a ‘secret’; it occupies some of the footprint of the Templo Mayor. This was one of the holiest sites in Tenochtitlan, devoted to Tlaloc (the Aztec god of agriculture and rain) and Huitzilopochtli (the god of war). You can still see its foundations next to the church.

There are more recent wonders, too. The Palacio de Bellas Artes – close to the leafy expanse of Alameda Central park – is an art museum as striking as the treasures inside it; a giddy mixture of Art Deco and Art Nouveau, crafted between 1904 and 1934. Its focus falls upon the same century; star exhibits include murals by Jorge González Camarena and Diego Rivera. The latter’s much more celebrated wife – Frida Kahlo – is also present.

Retail therapy can be sought in a range of tempting places – the department stores on the broad street of 20 de Noviembre in the Centro Historico; the haute-couture boutiques that decorate the Avenida Presidente Masaryk, where it sweeps through gilded Polanco.

Tastebuds can also be tantalised. While it is endlessly possible to lean on local staples – tortillas, tamales et al – 2024 brought the publication of a first Michelin Guide to Mexico, and with it, an even brighter spotlight on two of the capital’s most acclaimed restaurants. Pujol (pujol.com.mx), in Polanco, is the brainchild of Enrique Olvera – offering a modern slant on traditional Mexican dishes, all delicate tacos and palpable finesse. It is one of just two restaurants in the guide to have been handed two stars; the other is its Polanco neighbour Quintonil (quintonil.com), where chef-couple Alejandra Flores and Jorge Vallejo have also reinvented the national cuisine, with nine-course tasting feasts and fabulous mezcals.

Sleep can also be stylish and elegant. Perhaps at Condesa DF (condesadf.com), in the lovely neighbourhood of the same name – a design hotel, slotted into a neoclassical 1928 apartment building, whose rooms have been shaped by Mexican architect Javier Sanchez and Iranian-French interior designer India Mahdavi. Elsewhere, the St Regis Mexico City is a well known silhouette on the skyline (marriott.com) and boasts a perfect location. Its in-house spa deals in widescreen views of the cityscape, while its pool floats above the hubbub on the 15th floor; its King Cole Bar – one of the city’s best options for cocktails if you want to recreate Queer’s tippling – is a softly lit refuge from the commotion of Paseo de la Reforma outside.

If that busy boulevard (Paseo de la Reforma is an equivalent of Paris’ Champs-Élysées) looks familiar, it should. This was the very street catapulted to global attention by that spectacular Spectre opening sequence. Even if, again, sleight of hand was at play. Like Guadagnino’s CDMX (local slang for Mexico City), the ‘Dia de los Muertos’ carnival displayed with such verve was actually an intoxicating invention for cinema. No such event existed in reality. But it has since – by popular demand – been slotted into the city’s calendar, for visitors wanting to taste the reality of what they saw onscreen. In Mexico City, real life and cinema are so tightly entwined that one frequently influences the other.

Words by CHRIS LEADBEATER