Sean Penn is a man of many parts: Oscar-winning actor, writer, director, campaigner. Just don’t call him an activist. He dislikes the term, considering it devalued. Or a multi-tasker (‘the very idea makes me puke’). In truth, he is a reactivist, lending his celebrity muscle – both literally and figuratively – to any situation he feels will benefit from his involvement. He rolled up his sleeves and pitched in post-Katrina in New Orleans, in the horrific aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti (where he lived on the ground, literally, in a tent for nine months) and across the whole pandemic in the United States, where he promoted both testing and mass vaccination. Very much on his mind right now are the terrible events unfolding in Ukraine.

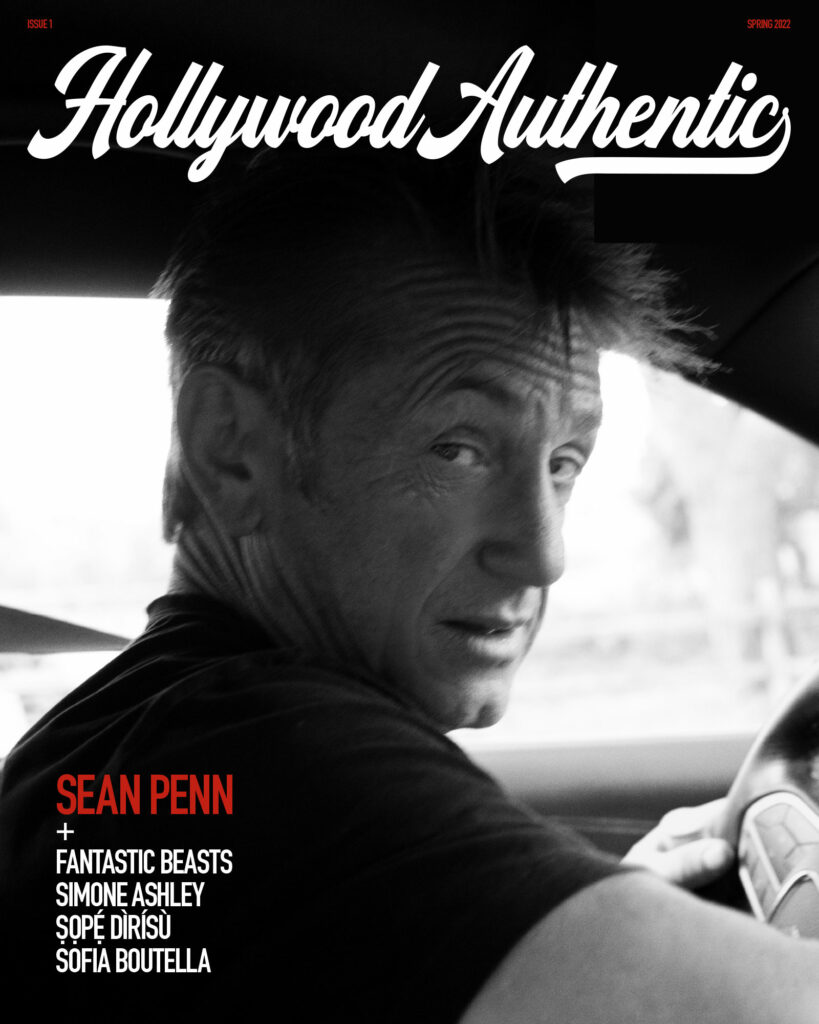

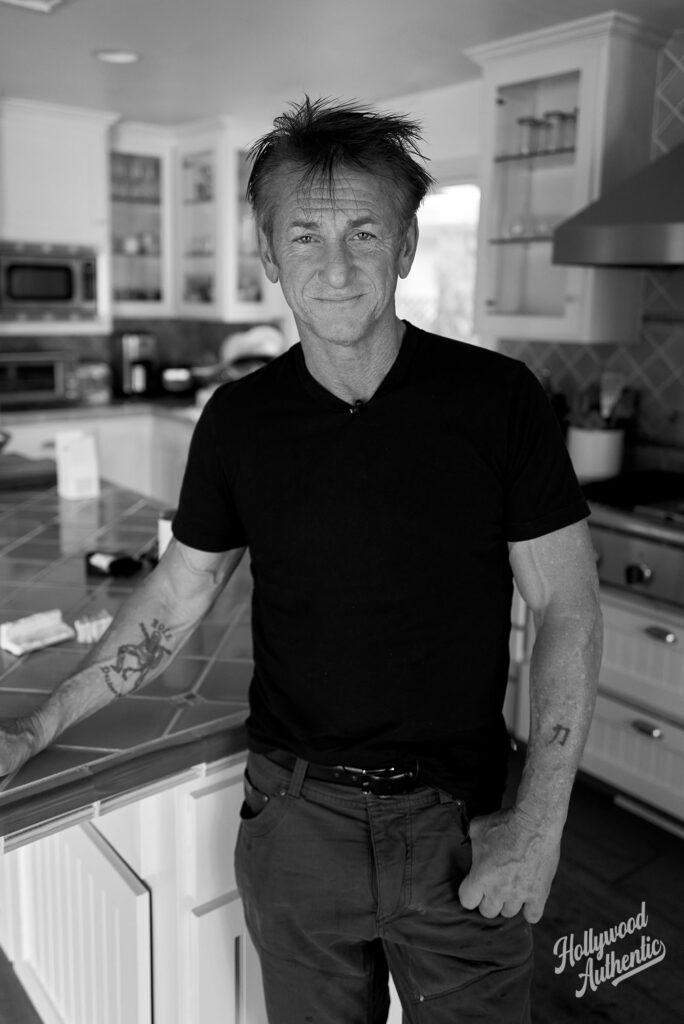

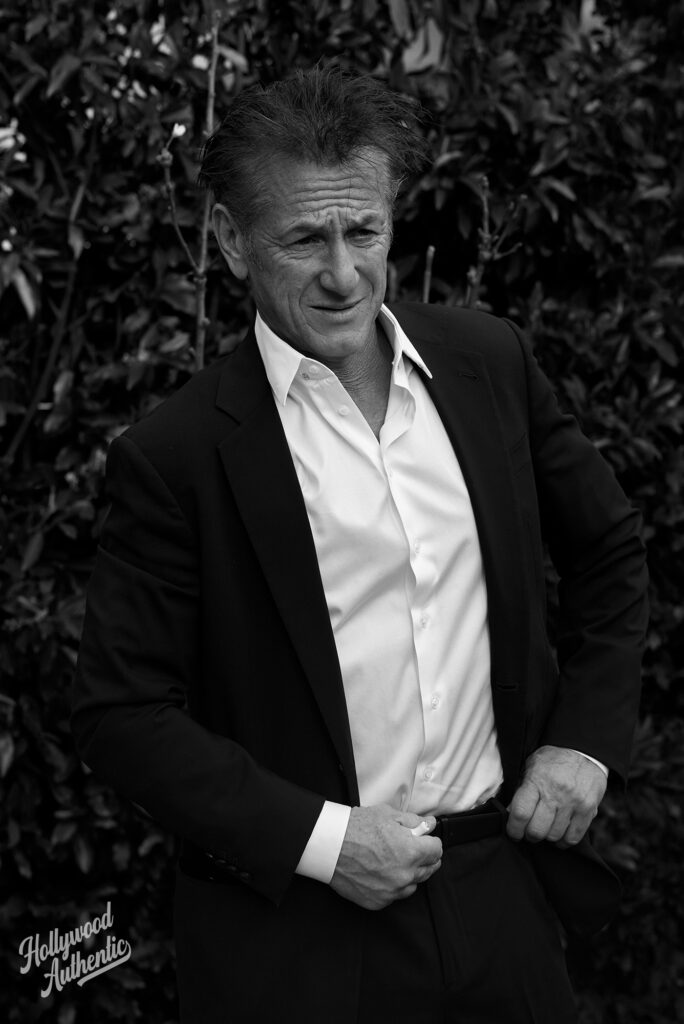

I recently spent a day with Penn, who is now 61. He is excellent company – intense, engaged, candid and, yes, funny. He talked at length about his humanitarian work, his father, the pressures of celebrity culture, the glue that binds his acting, directing and disaster relief efforts together, and his wife Leila George, whom he clearly loves very much. Even though they are going through a divorce. Nothing is entirely straightforward with Sean Penn.

During our time together, he drove me around Los Angeles, showed me his Malibu neighbourhood, his parents’ place and his house. Here I was struck by the wall of family pictures and the room where he keeps his many awards. What suprised me was just how many of the latter there were, not only the two Academy Awards (for Milk and Mystic River) and various critics’ gongs for those and Dead Man Walking and Into the Wild but also for his work outside the movies. He has been awarded the Hollywood Humanitarian Award and the Producers Guild Stanley Kramer Award (for “Illuminating provocative social issues”), the Peace Summit Award (decided by Nobel Peace Prize laureates), won The Alliance of Women Film Journalists Humanitarian Activism Award (shared with Sandra Bullock), been declared, with Ann Lee, Variety’s Entertainment Philanthropist of the Year, received a raft of awards and commendations from the US military and even been knighted by the Haitian president.

He is, of course, aware of how much sneering, sniping and cynicism his interventions, both physical and vocal, have generated in some quarters of the media. Accusations of grandstanding, poverty tourism and white saviour syndrome have dogged him over the years. In most cases he has heard it all before and it is water off a duck’s back because Penn knows exactly why he is drawn to troubled parts of the world. He does genuinely agonise about how much of a difference he can actually make, but as he said when he was pulling people through the filthy waters of a flooded New Orleans: ‘You have to do something.’

When we met, Penn had just returned from war-blasted Ukraine, where he met with President Zelensky. He was clearly moved and angered by what he had witnessed and his admiration for the people trying to hold off the Russian invaders shone through. Again, he fretted over whether making public appearances and documentaries (he was filming for Vice while he was there) was enough and whether, if it came to it, he would take up arms.

One person who believes that Penn’s presence was a positive is Zelensky himself. After he visited the capital, the president’s office issued this statement: ‘The director specially came to Kyiv to record all the events that are currently happening in Ukraine and to tell the world the truth about Russia’s invasion of our country. Sean Penn is among those who support Ukraine in Ukraine today. Our country is grateful to him for such a show of courage and honesty.’

What follows has been lightly edited for length and clarity, the section introductions and anything in square brackets are mine but, for the most part, this is Sean Penn in his own words.

ON PRESIDENT ZELENSKY

Penn can’t hide his admiration for the man who won the popular vote on an anti-corruption platform in 2019, praising his ‘passion and courage’. I suggested we hadn’t seen such powerful leadership in decades. He agreed, but also explained he thought it was a case of cometh the hour, cometh the man.

SP: I originally met him on Zoom, before the threat of more than the border war became real. This was early on in the pandemic in the US. We first started discussing a potential documentary about his country that wasn’t focused particularly on the war. And since then there’s been a lot of exchanges between us. Then I went and met him face to face the day before the invasion. And I was with him during the invasion, on day one.

I think back to the guy that I met before the Russians came. He was very charming, and very bright and very charismatic, and I immediately liked him a lot. But I don’t know if it served anybody’s reality to be convinced war was going to happen at that point. And it wasn’t as though it was going to make any sense if it did. So, you would reserve some part of you to hope that reason prevails. I’m speculating, of course. And if you are convinced that war couldn’t or wouldn’t happen, you are not fully challenged with the incredible burden and the incredible demand of courage, otherworldly courage, that it would take to be the president of that country in those circumstances. So, seeing Zelensky the day before invasion, I would say, it serves to reason that he would not have felt fully tested. And then seeing him the next day, it struck me that I was now looking at a guy who knew that he had to rise to the ultimate level of human courage and leadership. I think he found out that he was born to do that.

You must remember, Zelensky wasn’t always universally popular before this war. There was that guy who was going to run against Zelensky in the next presidential election and who was polling pretty damn well and had a real chance. One of the Klitschko brothers [Vitali], who had been world heavyweight boxing champion and was mayor of Kyiv. I spoke to him in November for the documentary I’m doing. This was long before the invasion, but we know that the war has been going on for years at the border, since the annexation of Crimea and so on. And there was a lot of criticism of President Zelensky in there. I don’t mean that in a disparaging way, it’s just politics. Well, what’s the mayor doing now? He signed up to serve under his commander-in-chief, President Zelensky. That’s how unified that country is now. That’s Zelensky’s legacy.

ON THE UKRANIAN RESISTANCE

Penn refers here to a compelling 2015 documentary called Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom (Netflix). It is about the peaceful protests in 2013/14 that turned into an uprising, where the Ukrainian riot police (Berkut) beat protestors mercilessly and eventually fired on them, deploying snipers as the people tried to tend to the wounded. The resilience shown in the film helps put today’s Ukrainian resistance in context.

SP: When we’re talking about the biggest picture of all, the biggest, most important [group of people] in our lifetime as an aspiration is the Ukrainian people. The Russian intelligence agencies must have looked at their stubbornness and resistance and said: ‘But it can’t sustain.’ Well, in the short term, the next few weeks or months, that’s a no-brainer. Yeah, it’s going to sustain. Go back to 2014, because they showed the world who they are back then. And so when you watch Winter on Fire, it’s a very easy transposition into today.

I’ve been to Ukraine twice. I’ve been in Mariupol. I was at the frontlines in Mariupol in November [2021], since when it’s been incredibly assaulted by the Russians. I’ve spent time in Kyiv, in Lviv, everywhere in between. But you don’t even need a passport to appreciate what’s important for us to understand – just watch Winter on Fire. It might be about the people in 2014 but they’ve been the same people every single day and never more so than now. They are together like never before and, as I said, that’s the historical legacy of Zelensky, because he’s the man who did it. They’ll never be able to take it away from him that he unified the Ukrainians to fight for their country.

ON HIS FATHER

Sean idolised his father Leo Penn, who died in 1998. He has credited Leo with instilling in him ‘pride of service’ and the desire to give something back to society. Leo served in WWII, then became an actor, appearing in several movies before being blacklisted for alleged communist sympathies and refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Penn senior subsequently became a director, working on classic TV series such as Columbo, Star Trek, Magnum PI and Little House on the Prairie. Sean got his first exposure to the acting life on the sets of such shows. Given the situation in Ukraine, and that the morality of armed conflict was very much on Penn’s mind, I asked him about his father’s war service.

SP: He wanted to be a pilot. But at that time in World War II they were training pilots who had never flown aircraft before in just eight weeks. This was to fly the Liberators [the Consolidated B-24 Liberator was a four-engined heavy bomber, nicknamed the Flying Coffin because it only had one exit for the crew of 10]. And, in the final stages of your training, you would have to pass a soloing test and he crashed the plane. Obviously, he survived it. But, once you fail that test, you’re not going to get another shot.

So, he became a tail gunner and a bombardier in a B-24 with a crew in the 775th Squadron [of the 458th Bombardment Group of the USAAF’s Eighth Airforce] called McNamara’s Band, named after the pilot [also after a popular song – there was a B-29 of the same name serving in the Pacific]. Myron McNamara became a top tennis coach, scout and pro player after the war, touring with the likes of Pancho Gonzales and Lew Hoad [he was also one of the first to spot Jimmy Connors’ potential]. My father’s group were flying low-altitude missions over Germany at night. They were stationed in London. They could be called out of a pub to go on a last-minute sortie at one in the morning. So, they’d get on the plane and hit the oxygen masks and clear their heads of the booze and go to bomb Germany.

And it was a seven-mission life expectancy. The first seven missions were not voluntary. You had to do it. After seven missions it was voluntary, because the life expectancy was so short. They broke the record, in terms of the volunteer flights. They flew 37 missions in all. Incredible.

They were shot down twice. And, in both cases, they were able to get the crippled aircraft, the Liberator, over allied lines before bailing. So, the second time it was winter and the fuselage had been blown out and my dad’s hands were frozen to the tail gun. And, like out of a movie, McNamara stayed on board until the last of the crew, other than my dad, was out. Then he went back and pulled my dad off the tail gun, virtually tearing the skin off his hands. And then they jumped. And they survived. So, obviously, in our household Myron McNamara and my dad were heroes, with the medals to prove it.

And then I started playing competitive tennis when I was a teenager. I was pretty good, ranked 300 in the juniors in Southern California, which was the epicentre of the sport at the time. Whenever the best college teams were playing, you’d go. So, UC Irvine was playing Pepperdine and, in the programme, I saw that the coach of UC was this guy called Myron McNamara.

I went up to him at the break and said, ‘Excuse me, coach, do you know Leo Penn?’ And he looked at me and he said, ‘Are you Leo Penn’s son? You get that motherfucker on the phone right now’. And I called my dad on a payphone and Myron said, ‘Get down here’. My dad came along and they stayed close friends till they died. Myron passed first and then my dad a couple years later, aged 77.

ON PROCESS

I wanted to get away from wars, both old and new, for a few minutes. So, I asked Penn about the process he uses to cope with wearing so many hats and the different tools he needs to fulfil his many pursuits, from being a Hollywood movie star to managing refugee crises.

SP: I’m not overlapping different projects like I once did, which took away from me, my work, my beliefs, people I care about in a lot of different ways that I wasn’t even aware of.

But all the things I’ve got to be a part of – from movies to travelling to Ukraine – all seem like part of the same structure to me. It’s like you are building a house. I know how to bang a nail through wood, I know how to measure the wood and cut it. I know how to build basic things till somebody who knows better gets there to. In the same way, I know how to lay a foundation as an actor, as a disaster relief worker, as a founder of an organisation or whatever. As a director, as a writer in film, they’re all the same thing.

You’re making a movie, it’s exactly like making disaster relief, although the stakes are higher in disaster relief. Same toolkit, basically the same job, just that you get presented with different architecture by the different architects that you work for as a builder.

ON CHARACTER

Penn has played a wide range of characters, from murdered gay mayor Harvey Milk to murderer Matthew Poncelet in Dead Man Walking. I wondered if there was anything that linked his choice of people to portray.

SP: It sounds like I’m trying to be fancy, but it’s about choosing roles that have clarity about the times in which you live. In my case, I think the best answer is that I chose the roles, when I could, which represented an area of life I was actively asking questions about – about being human or about something culturally or politically current. Something I was actively interested in, I guess, is the simplest way of putting it, not what I’d done before but something that felt important to me, so that I wasn’t answering an old question that I’d already come up with a satisfactory answer to. I think most of the projects that I’ve directed or wrote or adapted or played a role in the writing of were things about the questions eating at me at that time.

None of this is a purist thing. It’s just what it is. There’s a David Bowie documentary called Bowie, by Brett Morgen, which is due out this year. Bowie makes the point that artists should also try to make a good living, even though those that do are often called sellouts. He says, ‘I never thought that poverty was purity and I would never take anything away from an artist because they made some money.’ I get a lot of credit for being a purist, which is not what I was. My career is basically stumbling through, trying to build a single structure in a way that, once people look back at its form, they can say: ‘Oh, that’s what that guy was about.’

ON MARRIAGE AND VODKA

Penn has been married three times, and during his first marriage was famously driven to distraction by stalking paparazzi, sometimes striking out in frustration. ‘I just wanted to be an actor. I didn’t want to be the poster child for rebelling against the paparazzi,’ he told me. During our time together he visited his current wife (apparently soon to be his latest ex), Australian actress Leila George, whom he was clearly still very fond of, blaming himself, his commitment to outside causes and his antipathy towards the Trump administration for the rift.

SP: There’s a woman who I’m so in love with, Leila George, who I only see on a day-to-day basis now, because I fucked up the marriage. We were married technically for one year, but for five years, I was a very neglectful guy. I was not a fucking cheat or any of that obvious shit, but I allowed myself to think that my place in so many other things was so important, and that included my place in being totally depressed and driven to alcohol and Ambien at 11 o’clock in the morning, by watching the news, by watching the Trump era, by watching it and just despairing.

And as it turns out – this is going to shock you – beautiful, incredibly kind, imaginative, talented young women who get married to a man quite senior to them in years, they don’t actually love it when they get up from their peaceful night’s sleep and their new husband is on the couch, having been up since four, watching all of the crap that’s going on in the world and has decided that 10:30 in the morning is a good time to neck a double vodka tonic and an Ambien and say, ‘Good morning, honey. I’m going to pass out for a few hours and get away from all this shit.’ As it turns out, women as described, they don’t love that.

I don’t know what’s going to happen with us, but I know that this is my best friend in the world and definitely the most influential, inspiring person, outside of my own blood, that anybody could ask to have in their life. So, now, when I wash the dishes, I don’t answer my phone. If I’m with my wife for a day, I don’t have my phone on, even though I’m juggling a lot of things. I don’t juggle them better by taking more calls. I can have my phone off and not watch the news for 12 hours now. And even when I’m stressed, I’m never stressed the way I used to be. Because we’ve all had our heart broken at some point. So, if I get a call asking for my help, I know it is important to the caller, but now I think about my end, its impact on friends and family. I’m dealing with the micros now, not the macros. Although I still need vodka and an Ambien to get to sleep at night, I don’t use them to hide from the world now like I used to. I hope I’ve learned not to let everything overlap with me anymore. And that I really put priority in my family, in my wife, in my life, in ways that I can plan and control. That’s the theory, anyway.

ON GOING BACK TO UKRAINE

Penn mentions the CORE (Community Organized Relief Effort) non-profit organisation here, which he co-founded with CEO Ann Lee during his time in Haiti. It operates in disaster and war zones, offering medical, food and infrastructure aid/advice. CORE worked in Puerto Rico following the devastating Hurricane Maria and North Carolina and Florida after the double blow of Hurricanes Florence and Matthew. It also runs Covid-19 vaccination programmes in the USA, Brazil, India and Puerto Rico and is at present in Poland offering help and support to Ukrainian refugees.

SP: Look, my intention is to go back into Ukraine. But I’m not an idiot, I am not certain what I can offer. I don’t spend a lot of time texting the president or his staff while they’re under siege and their people are being murdered. I’d probably send one message through the chief of staff. ‘Here’s what I’m looking to do that I think would be of value. You only have to answer me in one of two ways: don’t come or come and do what you’re planning, or come, but here’s where you could be more helpful.’

I’ve got plenty to do with CORE on the receiving side of refugees in Poland. I’m shooting more for the documentary, but I’ll be doing a last-minute assessment of what value that will have. People will argue this, and there’s a million debates that I understand, but long term, we don’t have any tangible evidence that documentaries really change anything. We just don’t. We only know they can give hope.

And then, at some point, CORE is going to have to try to cross over the border to add to the resources that are so short for those still on the Ukrainian side of the border. Now with CORE, of course, I’ve had a decade in war to establish leadership outside of my own, and I have great people. CORE doesn’t fall apart if that bus hits me tomorrow. In fact, my contribution now is principally to share their message. Yes, I get hands-on in periods of starting up, like when I go back to Poland or if we begin operating in Ukraine itself. By hands-on, it might be just morale boosting because people like knowing that the founder recognises what they’re doing. And some of them might be movie fans or whatever. But CORE is mostly run by Ann Lee now and by the other department heads throughout the world in the areas of operations where we work. Good people, all of them.

ON WAR

I photographed in a few hot zones when I was a kid. My first war, when I was 19, I got smuggled into Burma with the Karen guerrillas. When I was 23, I was in Grozny for the Russian assault in ’95. I went in on what was probably week three or four of the battle and it looked like what Kyiv could become in weeks from now. Smashed. The greatest relief in my life is that I decided I wasn’t going to do that sort of photography any longer. I asked Penn if he was apprehensive about going back into a war zone.

SP: Well, I’m never like a conflict zone journalist who stays months or years in a place that’s really sketchy, and never someone who had no choice but to be there and live there. Nor am I a soldier. Statistically, I’ve never really taken any risks at all. And that includes 2003 Baghdad, when I was on my own outside the Green Zone. I was there about five days. You probably had a one in 100 chance of getting killed.

The only possible reason for me staying in Ukraine longer last time would’ve been for me to be holding a rifle, probably without body armour, because as a foreigner, you would want to give that body armour to one of the civilian fighters who doesn’t have it or to a fighter with more skills than I have, or to a younger man or woman who could fight for longer or whatever. So, where I am in life is short of doing that, but if you’ve been in Ukraine [fighting] has to cross your mind. And you kind of think what century is this? Because I was at the gas station in Brentwood the other day and I’m now thinking about taking up arms against Russia? What the fuck is going on?

I think that we can be fascinated by conflict but also intellectually be very anti-war. If you have seen war, and I’ve seen a little bit of it, there’s a rite of passage while you are in or near it that has to do with some basic questions you ask yourself: how would I react? Could I keep enough oxygen in my brain to make clear judgements? Are you going to be damaged by being in a war, emotionally or psychologically? Because there is always a cost to you or your loved ones. I think that there is a certain part of my own pursuits that is influenced by those questions that on some level demand answering. And so, yeah, I think it would be just not honest if I said that wasn’t a part of it.

Sean Penn stars in the Watergate-based series Gaslit, out on Starz, the US TV network, premiering 24 April.

Support Ukrainian refugees now:

https://rb.gy/elgok5

Robert Ryan is a best-selling novelist and screenwriter, and in a previous journalistic life wrote for Arena, British GQ and The Sunday Times