Josh Hartnett takes Greg Williams to the pub.

In 2020, Cate Blanchett and I sat in the back of a car at a locked-down Venice Film Festival – where she was president of the jury – and discussed the idea I had for a magazine. She suggested a shoot with her chickens and I imagined what that would look like on the cover of Hollywood Authentic.

It was 2022 when we published our first issue; Sean Penn kindly agreed to be on our cover. Since then, I’ve continued to imagine that shoot with Cate and her chickens. Six months ago, my wife Daisy designed a gown inspired by Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep for our fledgling Hollywood Authentic clothing range. We knew who we wanted to see in it and announced to the team that our dream was that Cate would wear it in a pair of muddy wellies holding a chicken in her potting shed. We got on with manifesting it. Fast forward to a serendipitous encounter at Glastonbury and hey presto…

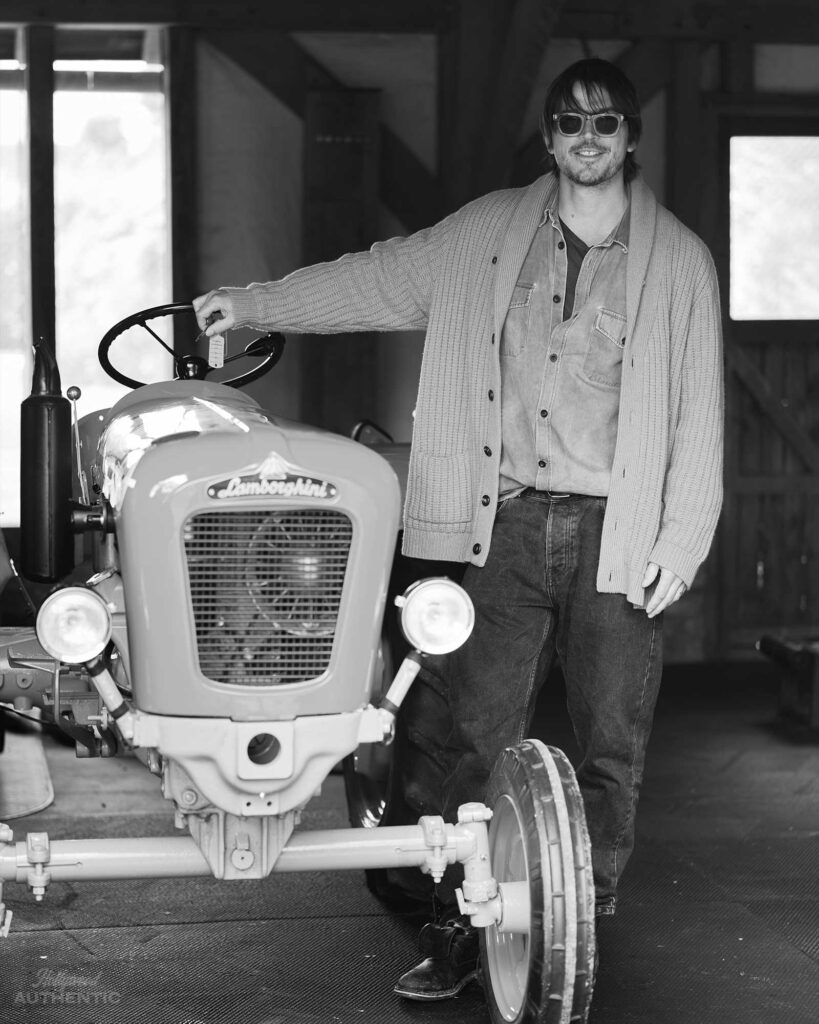

This issue represents another example of artists showing their generosity in inviting me into their lives to show an unseen side of themselves. Generosity and motion is what links all our subjects in this issue; they’re driving kid’s electric jeeps (Cate), vintage tractors (Josh Hartnett) and Ferrari race cars (Nicholas Hoult) while talking about what propels their passions and careers.

For this issue we also invited more collaborators into the Hollywood Authentic family. I met portrait photographer Charlie Clift at BAFTA a couple of years back and was immediately impressed by his work – he captures Lennie James for “a little nonsense”. We’re also thrilled to have Stephen Merchant guest-write his love letter to a Hollywood classic, Double Indemnity. Our now regular contributors are back: Gary Oldman and Gisele Schmidt write about the work of legendary Hollywood photographer Sam Shaw, Abbie Cornish gives us a review of Toronto Mexican restaurant Quetzal and Arianne Philips interviews veteran costume designer Albert Wolsky. Mark Read is also back turning his masterful lens to the Marin County Civic Center.

We’ve come full circle from that chat in Venice 2020 as we bring this issue to Venice 2024. I can’t wait to see what we take to the floating city in years to come…

Greg Williams, Founder, Hollywood Authentic

Photographs, interview and video by GREG WILLIAMS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

Josh Hartnett may reject the idea of being a ‘movie star’ but he does have a Lamborghini stashed away in the barn of his English country home. A vintage model that he’d dreamed of owning and managed to snag at auction, she’s a 1965 blue-and-orange machine that he calls ‘The Beast’. And she does a top speed of just 5mph. ‘I feel like a very budget Steve McQueen,’ he laughs as he unveils his restored Lamborghini tractor and strokes the polished metalwork. ‘He would be leaning on his Ferrari, and I’m leaning on my tractor…’

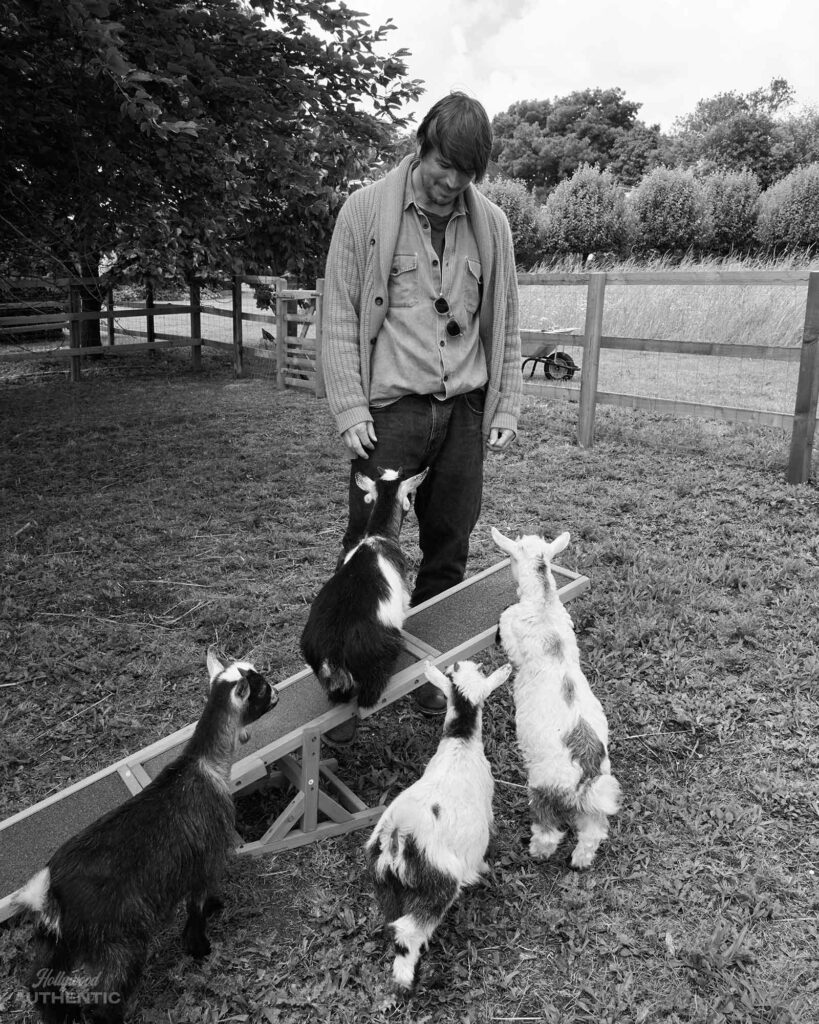

Though born and bred in Saint Paul, Minnesota and having worked all over the world during his 27-year acting career, Hartnett has found a contentment in the English countryside an hour’s train ride out of London, living with his wife, actor Tamsin Egerton, and four young children. The family share their home with four pygmy goats, six Silky bantam chickens, guinea pigs, a bulldog called Bear and a backyard big enough for Josh to learn about the land from the neighbouring farmers and warrant a gleaming orange tractor. His life, he jokes, is ‘fairly analogue’. He chugs out of the barn and down the field on a blustery July day. That sense of fulfilment is also mirrored in his work, having recently been a part of box-office and awards phenomenon, Oppenheimer, and now opening the new M Night Shyamalan water-cooler thriller, Trap – playing a serial killer trying to escape police at a pop concert.

‘I’ve always been attracted to directors who are working in their own realm – some of them outside of the system, some of them within the system, but always doing something that feels very authentically them,’ Josh says of his career over coffee in his cosy kitchen, which shows his very real off-screen life via the baby cot and the dog crate taking up space in the room. ‘I’ve recently been lucky enough to work with those directors but on a bigger scale, and lots of people are interested in seeing them. And that’s the best of all worlds.’

Trying to find the sweet spot in work and the fame that comes with it is something Josh has been juggling since his first role in 1997 on TV show Cracker (a US adaptation of the UK Robbie Coltrane hit). Having moved to New York after art school to pursue acting as a teen, a trip to LA nabbed him the role that would propel him into the Hollywood system and a period of time when he was being marketed as a ‘heartthrob’. Roles in Halloween: H20, The Virgin Suicides, The Faculty, Black Hawk Down and Pearl Harbor followed, but his public persona chafed with his ambition and own sense of self.

I know it’s an odd thing to say as an actor, but I really wanted to do specific types of films, and I felt like I had the ability to do it because I got really lucky at a young age. So I used what little clout I had to create these films

‘Fame is not the endgame for me in any way shape or form. Money is good and great – you need it. You need to be able to make enough money to be able to survive. But if it becomes your be all and end all, I think that’s a trap,’ he says. ‘I’m not particularly interested in falling into those traps if possible. I’m very happy with my family and my life. I’ve got a lot of good friends. I try to keep it all in perspective.’

That resistance to the narrative crafted for him and belief in pursuing his own interests rather than following a rote route led to the now 45-year-old famously passing on an opportunity to play Batman in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight in 2008, when the actor and director met for a preliminary chat. Their conversation led to an interest in working together but not to Josh donning the famous cape. ‘I had an initial conversation with Josh but he had read my brother’s script for The Prestige at the time and was more interested in getting involved with that,’ Nolan recalled last year. ‘So it never went further than that.’

‘I didn’t do any of the superhero movies back when it was the inception of the modern superhero,’ says Josh. ‘Around the time Downey did Iron Man, there were a lot of new things happening but it was not really the route that I felt like I needed to go on. Personally, I didn’t want someone else dictating how I was portrayed in the media, and how I was portrayed on screen so much. I know it’s an odd thing to say as an actor, but I really wanted to do specific types of films, and I felt like I had the ability to do it because I got really lucky at a young age. So I used what little clout I had to create these films. Some of them were more successful than others. I heard a great quote from another actor. I had a film that wasn’t super-successful come out, and he said, “Look, you’re never as bad as they say you are, but you’re also never as good as they say you are. This is a business of extremes. People want to tell a story. It’s all narrative. Take it with a pinch of salt. Enjoy it when it’s working, but don’t take it too seriously when it’s not, and don’t ever get too excited about yourself.” So, all that said, I didn’t really want to be defined by other people. I wanted to do my own thing. That’s why I’ve created the career I’ve created.’

Part of the pulling away from the prescriptive ‘movie star’ persona was self-preservation. ‘It just felt like there was a lot of intrusion into my life at that point because I was a young actor, and people were interested in my life, and I didn’t know how to protect myself exactly at that point because I was young. And, also, I was still defining myself, in the way that we all do in our late teens or early twenties. So to have all these other opinions of who I was constantly swirling around in the miasma that is my brain while I’m trying to decide what it is that I want to be – it didn’t feel entirely healthy. So I just sort of took a step back, and tried to re-evaluate. The big machine wants you to do something very tried and true – something that they believe that they can reproduce or control. I wanted to try to do something that felt more authentic to me. I think, looking back on it, it was self-protective, but it was also much more positive than that. They wanted star-making. There were specific things that everybody in the industry wanted me to do, and I felt like I hadn’t signed up for that entirely. I just kind of felt like I wanted to be more myself than that.’

Though he didn’t take an official sabbatical or stop working, Josh moved physically and mentally away from Hollywood. ‘I’ve never really considered Hollywood to be the centre of my adult life. Even though I’ve been working in Hollywood my whole adult life, I’ve always thought of myself as being more spiritually a New Yorker.’ He laughs at himself. ‘“Spiritually” sounds so dorky and over the top. But I feel like I want to be around people from all sorts of walks of life. Especially when I’m not working, it feels unnatural to be constantly talking about work, or constantly talking about my own career. It feels too isolating, and it’s self-indulgent. In New York, most of my friends weren’t in the business, and still, to this day, my close friends aren’t in the business.

‘I love my job. I love acting, and I love making films – I guess I just never thought of our business as a fully catch-all lifestyle. It’s work, and I really enjoy the work, and I like to escape it and see friends and family in different places, and live in a different place. And all the travel, when you’re acting, has kind of lent itself to feeling like I could exist anywhere. So coming to the UK didn’t feel unnatural. Living here full-time doesn’t feel unnatural, as it wouldn’t feel unnatural to move to Morocco, where I was working for a long time, or Hong Kong, where I was working for a long time. It just always feels like, “Oh, this is the next step.” It doesn’t feel like it has to define you in any specific way.’

Honestly, I’ve become really fond of being here: the quiet, the still; all of it. It’s being much more aware of yourself and your surroundings. I’ve become enormously impressed by farm work, and how much people put into it, and how difficult it is

In 2011, Josh met Tamsin on the set of The Lovers and England became a place he visited more often, before moving between the States and the UK as they grew a family together. Then Covid hit and the couple made a decision to put down roots in the British countryside. They’ve been in a small village with an excellent local pub for two years now. ‘We’re sort of transplants from the city,’ Josh admits as we take a walk through the garden to the goat enclosure and the chicken coop, which borders the working farm next door. ‘We’re trying to get to know what it’s like to live in the countryside. And, honestly, I’ve become really fond of being here: the quiet, the still; all of it. It’s being much more aware of yourself and your surroundings. I’ve become enormously impressed by farm work, and how much people put into it, and how difficult it is. I grew up in cities – so all this is brand new to me. It comes with that sort of feeling of: “Is this my real life, you know?” Because it doesn’t feel like the rest of my life has felt up til now, so it’s all just fresh.’

As he introduces his goats (Olive, Lavender, Poppy and Grape) and the chickens that provide daily eggs, Josh considers his most recent projects and how he’s come full circle to actually engaging with the work that he always wanted to. He recently appeared in Black Mirror, just guest starred in Season 3 of The Bear (as Tiffany’s Taylor Swift-adoring fiancé) and was part of last year’s ‘Barbenheimer’ box-office phenomenon when he and Nolan finally worked together on Oppenheimer. Playing nuclear physicist Ernest Lawrence, Josh’s was one of the roles that spanned the decades throughout the film, which meant he worked opposite most of the cast and was on-set for most shooting days. ‘Chris is a singular filmmaker on every level – nobody tells him how to make his film. He’s a great example of someone who’s been able to create a sort of independent style of film with a massive budget, in the midst of a massive industry, and still have tons of people who want to see it. It’s a remarkable achievement. I could probably count on two hands the directors who could do that. I think [Trap writer/director] Night [Shyamalan] is another one. A director who’s been able to find a way to relate to the audience, and do it his way, now for 25 years. I feel incredibly lucky to be able to keep working with these guys.’

Josh doesn’t do social media and wants his kids to enjoy their tangible country existence over a virtual life lived through a screen. ‘You just have to be careful about how you introduce your kids to it, get a sense of where the information is coming from, and who they’re interacting with. And you have to be really clear about that. Otherwise, it’s the Wild West. It’s dangerous.’ He’s also aware that careers ebb and flow – that for every awards-magnet Oppenheimer, there’s a critically mauled Pearl Harbor – but equally that all films find an audience eventually. ‘Most of [my films] went unseen until many years later on Netflix. People tend to like them, and come up to me now, and say they really enjoyed the film. But our careers in this business – there’s so much luck involved. It’s so streaky. So when people start to find you interesting again, suddenly you’re being offered a lot of stuff that people are going to see. And when people are less interested, suddenly you’re offered nothing.’

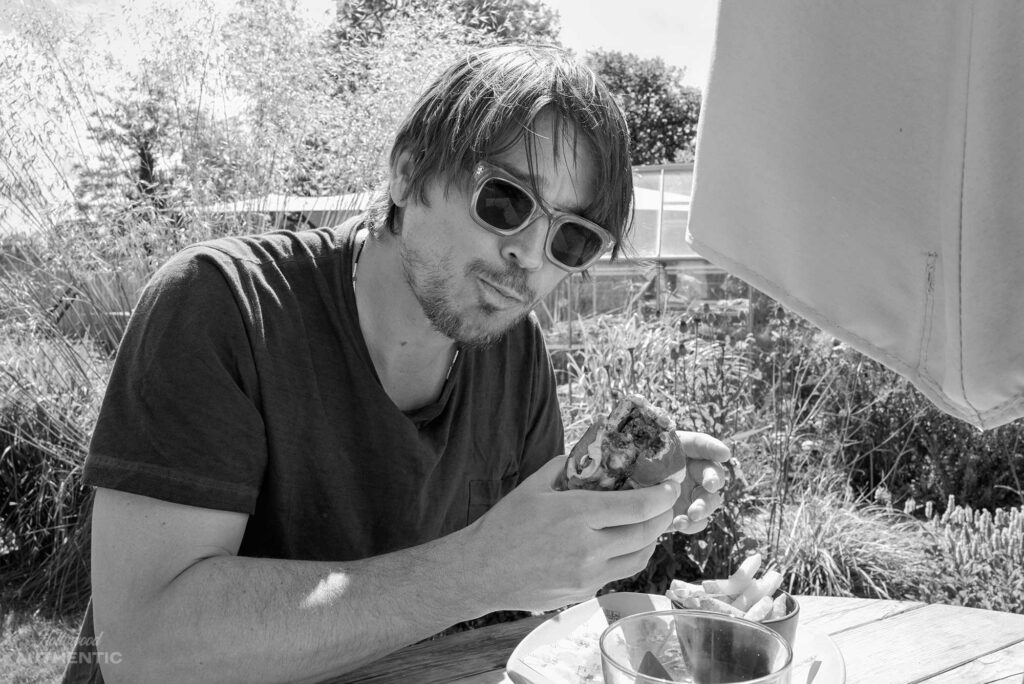

As we head out to the local pub for a burger and a pint, Josh spots my Porsche in his drive and asks to take it for a spin. As he negotiates twisting country roads with the wind in his hair, he recalls a high-speed former life before he settled down to fatherhood and the country. ‘I used to track-race Porsche cars all the time. I completely gutted 911s with the biggest engine you could get, completely light. A lot of fun. I took a Bugatti out on an F1 track in Kuala Lumpur. The straight is pretty full on. I don’t know exactly how fast I was going, but it was faster than I’d ever gone before…’ Quite the difference from the Lamborghini tractor that the actor has to switch off before putting in reverse in order to park it back up in the barn. ‘It can’t change gears while it’s driving,’ he explains fondly. The same certainly cannot be said for its owner, who changed his direction of travel mid-journey and arrived at a happier destination.

Josh Hartnett stars in Trap, directed by M Night Shyamalan, in cinemas now. Grooming by Charley McEwen. Josh wears own clothes and cardigan by Hollywood Authentic × N.Peal