Words by ALEX BILMES

Some films haunt us, obsess us, change our lives for having experienced them… This issue, the editor-in-chief of British Esquire extols the spellbinding virtues of Wong Kar-wai’s 2000 bittersweet modern classic.

Through the lens of a lesser director than the Hong Kong Chinese auteur Wong Kar-wai, In the Mood for Love might have been somewhat slight, and more than a little contrived. A newspaper journalist, Mr Chow, and a travel agent’s secretary, Mrs Chan, take separate rooms on the same floor of a cramped apartment block. They move in on the same day. Coincidence! Or, coincidence? Both are married to people who are often absent: Mrs Chan’s husband travels frequently to Japan on business; Mr Chow’s wife does shift work, so they are rarely at home at the same time. (Everyone in the film is defined – though, crucially, not everyone is confined – by their marital status.) Both Mr and Mrs are reticent, contained, solitary. They’re also both off-the-charts attractive, but we’ll come to that later.

Slowly, tentatively, first with glances and smiles, then halting, stiffly polite snatches of conversation, they come to know each other – and soon to discover something surprising. Mrs Chan’s husband is cheating on her, with Mr Chow’s wife.

‘By the way, haven’t seen your husband lately.’

‘Haven’t seen your wife lately, either.’

Not a terrible set-up for a movie. But hardly, you might think, the raw material for the most luscious unconsummated romance ever depicted on screen, a film as chaste as Brief Encounter, and yet also a gorgeous swoon of a work, one that has become regarded by critics and discerning audiences as perhaps the most hauntingly affecting love story ever made.

When Sight & Sound announced the results of its most recent poll, in 2022, asking movie insiders to nominate the greatest films of all time (the list, published once a decade, is not definitive, but it is highly influential and hotly debated – and has been since its debut in 1952), In the Mood for Love placed at number five. It came below Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) and Ozu’s Tokyo Story (1953) – and above every other film ever made anywhere or at any time. Quite good, then. Akerman’s victory was unexpected, but few cineastes were especially surprised that Wong’s masterpiece ranked so high. The film is by now an established classic, one of the wonders of world cinema.

I rewatch it every year and it loses none of its erotic charge. It is a film that takes nostalgia as one of its themes, and it is impossible to think of it without succumbing to an indulgent melancholy, a yearning for times past. When it ends, you want to go back to the start and relive it, like an old, unresolved love affair.

The film opens, mysteriously, with an epigraph:

He remembers those vanished years. As though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.

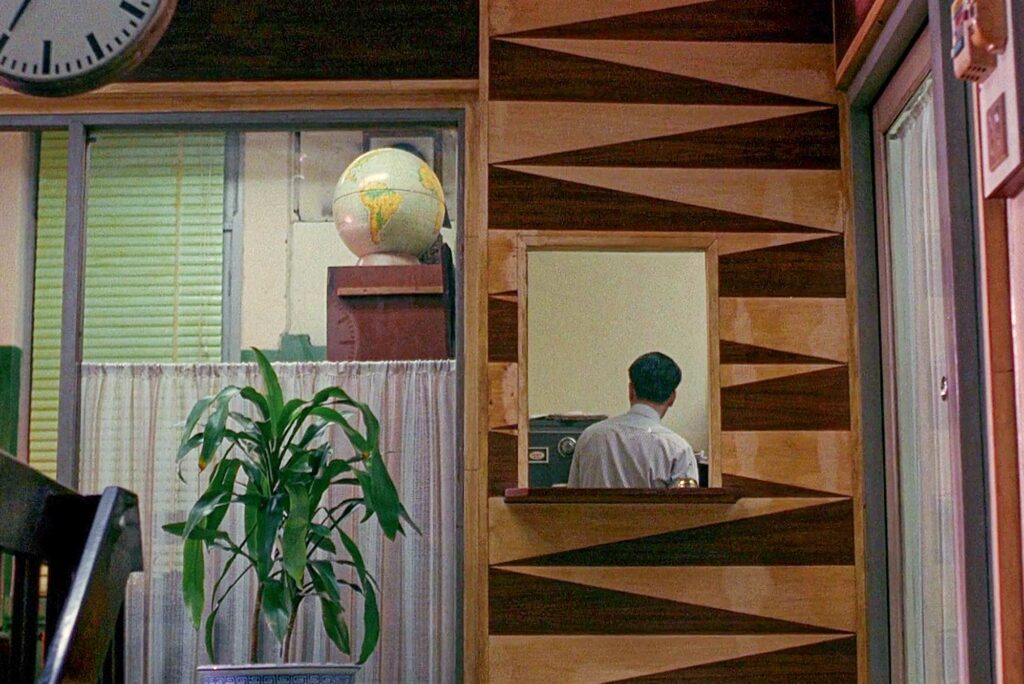

A second title card informs us we are in Hong Kong, in 1962. ‘A restless moment.’ Then we’re inside the cluttered apartment of Mrs Suen, a good-natured busybody, where a slender figure in a tight floral-print dress with a pinched waist and high cowl collar – which clashes appealingly with the floral-print curtains and the floral-print lamp shade – is being shown around, with a view to renting a room. This is Mrs Chan. It is evening. She has come straight from work. The building has seen better days. It is dimly lit, the walls are stained, the wallpaper is peeling. All this in stark contrast to the appearance of Mrs Chan herself.

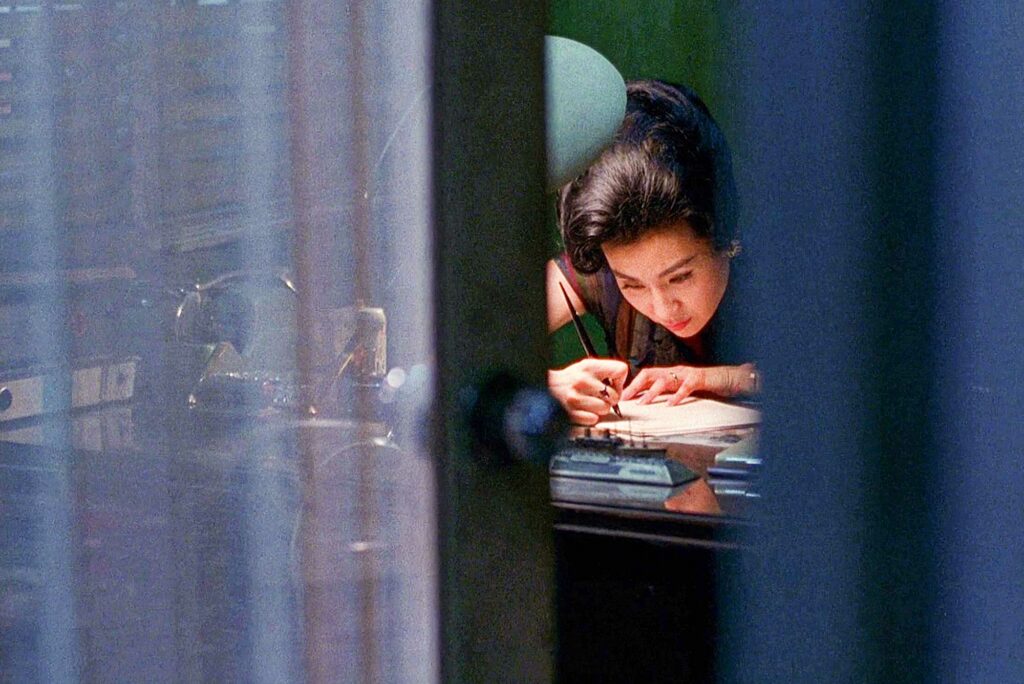

Where to start? As embodied by the actress Maggie Cheung, she is dazzlingly, heart-meltingly beautiful. A delicate, willowy young woman with supremely expressive, intelligent eyes and a face that catches the light from any angle. And Wong knows how to shoot her: tight, close, his roving camera placed at knee-height, hip-height, the better to follow her as she moves, to appreciate the contours of her shape.

‘You notice things if you pay attention,’ Mrs Chan says at one point. Wong’s camera notices everything: steam from a kettle, a spoon stirring a cup of tea, a billowing red curtain, the way plumes of cigarette smoke hang in the air, rain-slicked streets, the fogged windows of a taxi cab at night, the particular shade of lime on a dress. He shoots interiors like a spy, lingering briefly on a detail, moving on. We in the audience feel ourselves to be inside the frame. Not merely voyeurs – although certainly that, too – but silent participants in the action. We, too, are falling in love.

Next shot: seen from behind, in shadow, a man climbs a shabby staircase. He arrives into a corridor and steps into the light. Get a load of this guy: matinee-idol handsome, hair slicked back, immaculate silk shantung suit, crisp white shirt, tie. But there’s something mournful about him, something wounded, a vulnerability. It’s intriguing, and it’s sexy. Mr Chow is played by the great Tony Leung, that most understated of leading men, and perhaps only he could have the magnetism to share a screen with the exquisite Maggie Cheung and not vaporise under her flashbulb glare.

OK, so now we’re sold. Spellbound. Who cares about the script or the plot when we can spend the next 90 minutes in the company of these two heavenly creatures? When we can stare at Tony Leung smoking in the rain, or Maggie Cheung sauntering in slow motion through the soupy humidity of a crumbling, crepuscular city. When we can listen to the composer Michael Galasso’s aching score for cello, and to the languorous, enveloping sound of Nat King Cole singing ‘Quizas, Quizas, Quizas’. Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps…

But In the Mood for Love, for all the aesthetic bliss it offers, is more than a superficial exercise in atmospheric filmmaking. It is a study in longing and desire and a meditation on time, loss and regret. In its surface is its depth.

As the plot thickens, the film becomes more dreamlike, impressionistic. It gets stranger and stranger. Mrs Chan and Mr Chow begin to roleplay their spouses’ infidelity. At a restaurant, he orders what her husband might have had, she wonders what his wife would eat. He takes her hand and asks if they should stay out all night. But her husband would never say that, so they play the scene again. This time she makes the first move, simpering a little. It’s a dangerous game.

‘I didn’t think you’d fall in love with me.’

‘I didn’t either.’

He’s moving to Singapore. They rehearse a final farewell. She cries on his shoulder. Who knew it would hurt so much?

Will she go with him? Is it too late? Have they missed their chance? Will their affair, if that’s what this is, ever be consummated?

I won’t tell you that part in case you haven’t seen it. Enough to say that the film’s final, peripatetic, time-skipping sequences are gripping, tender and devastating.

In the Mood for Love is, loosely, the second part of a trilogy, beginning with Days of Being Wild (1990) and ending with 2046 (2004). Both those films have much to recommend them but neither comes close to the power and potency of Wong’s masterpiece. But then nothing does, and none of the cast or crew – cinematographers Christopher Doyle, Pun-Leung Kwan and Ping Bin Lee; production designer/costume designer/film editor William Chang; composer Galasso – for all their many decorations and achievements, would ever work again on a movie so enduring and beloved.

‘That era has passed,’ reads a title at the end. ‘Nothing that belonged to it exists anymore.’

Images courtesy of BLOCK 2 PICTURES/JET TONE CONTENTS

A special 20th anniversary 4K restoration is available exclusively on MUBI