Photographs by MARY ELLEN MARK

Words by GISELE SCHMIDT & GARY OLDMAN

Hollywood Authentic’s photography correspondents Gary Oldman and Gisele Schmidt look at the work of an award-winning documentary photographer with a personal connection to their meeting.

Gary and I are ever grateful to Greg for allowing us to grace his pages with our little stories and it gives us great joy when he asks, ‘Who’s next?,’ for us to blurt out a name that has impacted us so very deeply over the years. So when the question came around this time, we immediately responded; Mary Ellen Mark. And then, when we sat down to write, we were ultimately confronted by the blank page with the cursor mocking us as we realised where do we even begin? It’s Mary Ellen Mark, ffs!

Mark is recognized as one of the most respected and influential documentary photographers EVER. She has published 30 books and countless photographic essays in world-renowned magazines and journals and has received so many awards and commendations that it could fill this magazine twice over. How can we even touch the surface of the indelible mark she left on the history of photography? We can’t.

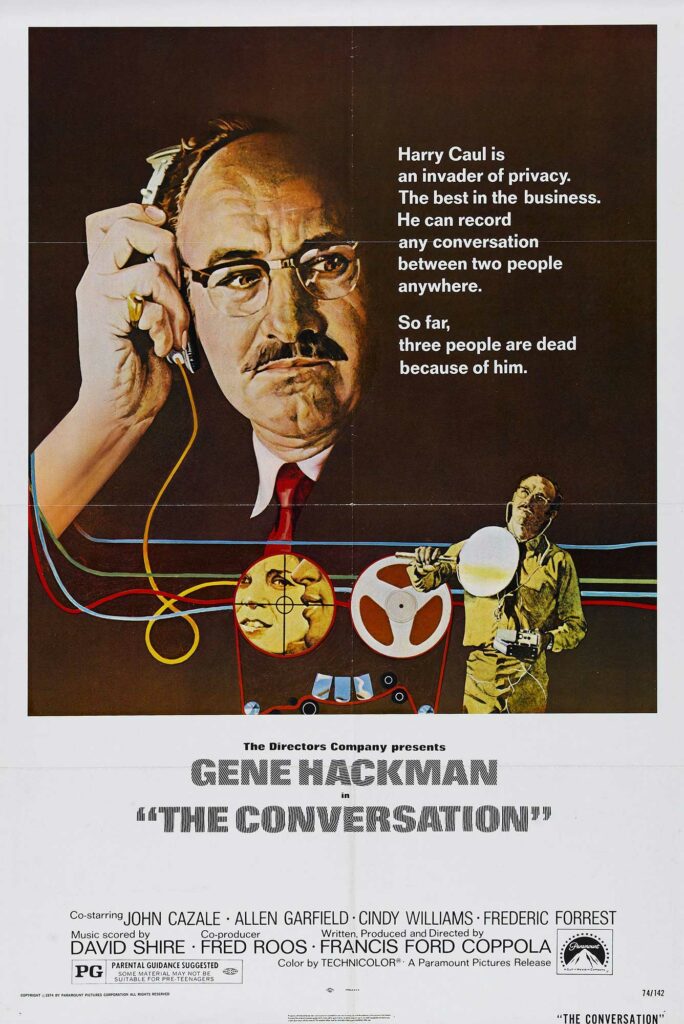

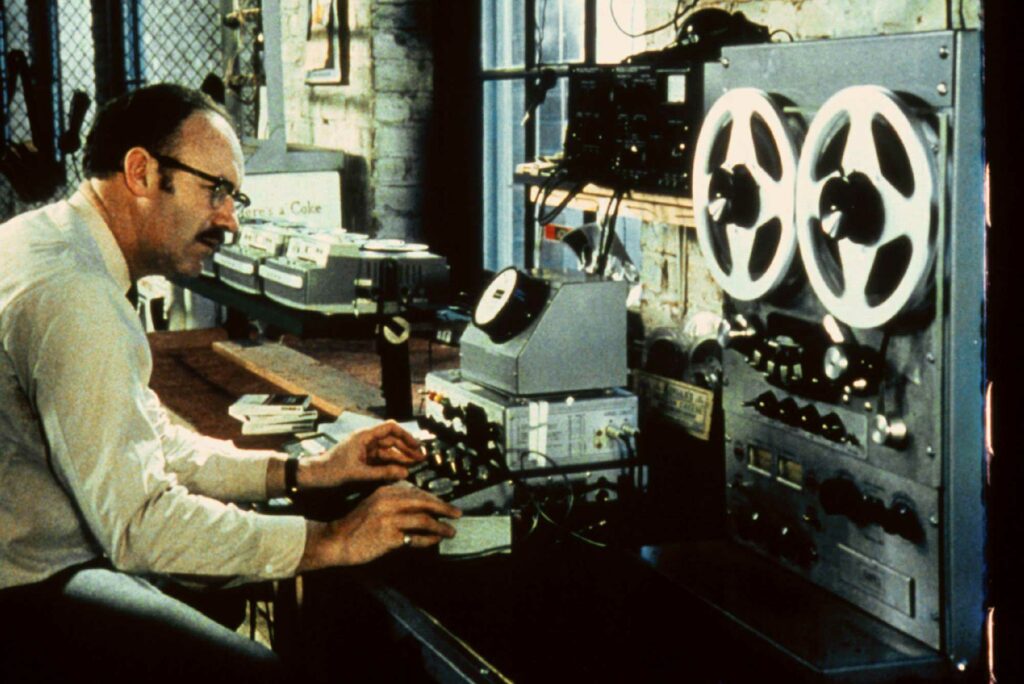

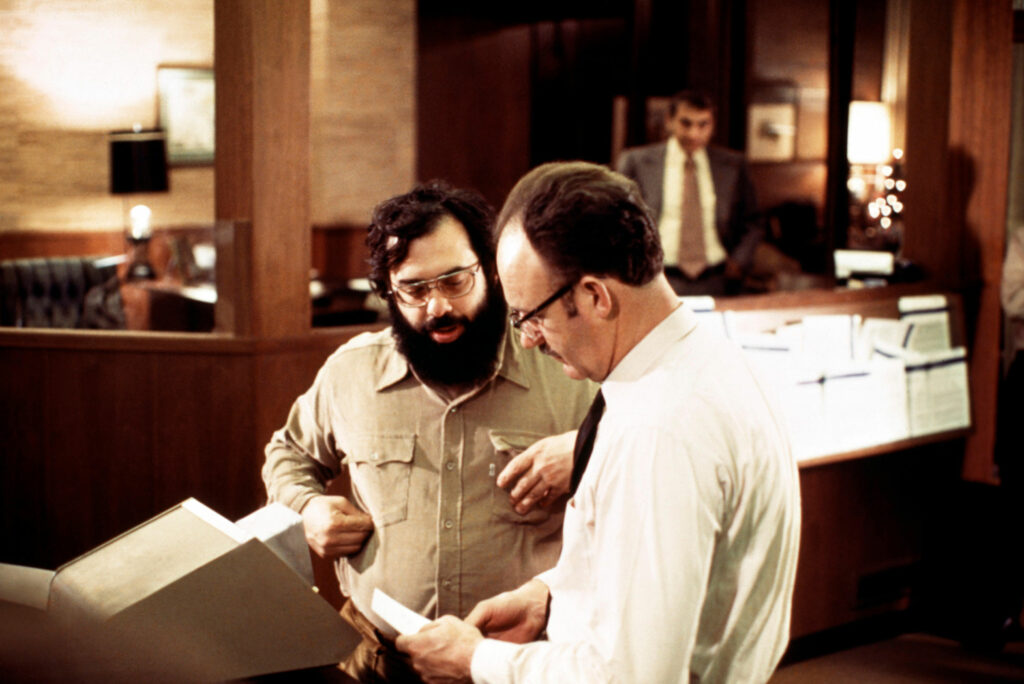

And why are we focusing on a photographer who documented the psychiatric patients of the Oregon State Hospital, the street prostitutes of Bombay, the teenage runaways of Seattle, or Mother Teresa’s Mission of Charity work in Calcutta? Because Mary Ellen was also the stills photographer on over 100 films from the 1960s to 2000s… Fellini Satyricon (Frederico Fellini, 1969), Mississippi Mermaid (François Truffaut, 1969), Tristana (Luis Buñuel, 1969), The Day of the Locust (John Schlesinger, 1975), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Milos Forman, 1975), Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979), Tootsie (Sydney Pollack, 1982), Silkwood (Mike Nichols, 1983), Agnes of God (Norman Jewison, 1984), American Heart (Martin Bell, 1993), Sleepy Hollow (Tim Burton, 1999), Babel (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2006), Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus (Steven Shainberg, 2006), Australia (Baz Luhrmann, 2008), to name just a few.

Mary Ellen Mark brought the same exceptional sensitivity and humanity to her work on movie sets that she did to the subjects documented in her photo essays. With her photojournalist’s eye, Mark’s photographs provide insight to life on set and the personalities of some of the foremost directors and distinguished actors of our time. With the release of Mark’s publication, Seen Behind the Scene (Phaidon Press, 2008), the Fahey/Klein Gallery held an exhibition commemorating this body of work. I had met Mary Ellen a handful of times through the gallery, but during this particular show, we spoke about narrative. Each frame should stand on its own; like a character, but when looking at a roll, it should tell a story, like a film. This conversation was years prior to meeting Gary and consequently well before he encouraged me to pick up my camera, but it is something I consider whenever I click its shutter.

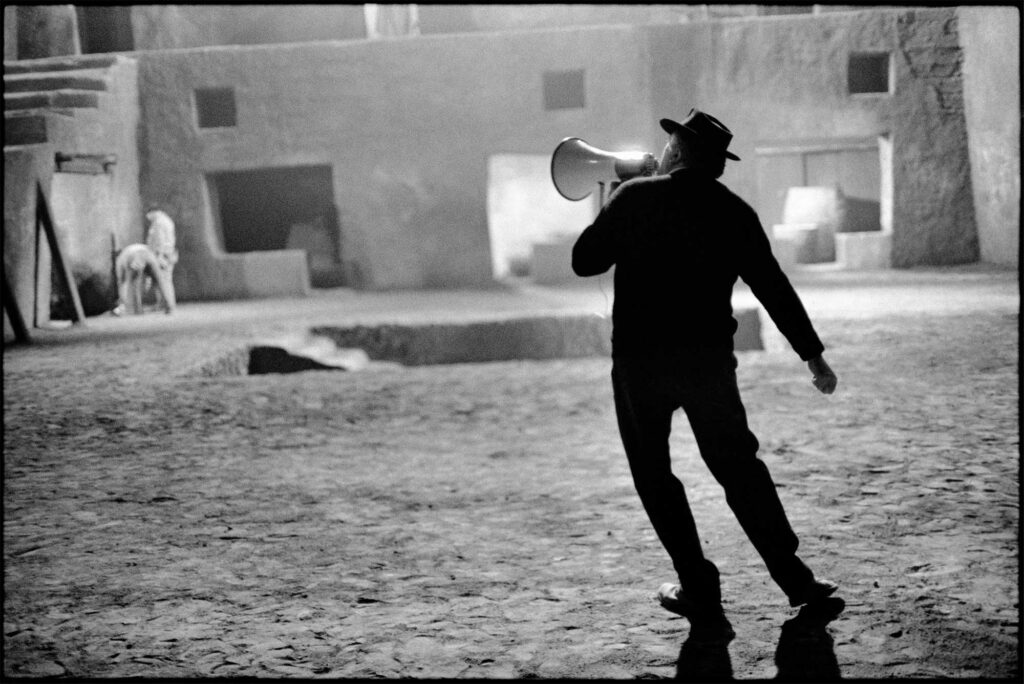

We find that this idea is personified in Mark’s portrait of, Fellini on the Set of Satyricon, Rome 1969. Mary Ellen Mark recounted how Fellini was one of her favourite directors and that something amazing would happen every day with him while on set, ‘Fellini was wonderful in front of the camera. The picture of him with the megaphone was taken as he supervised a new set being built. Even though this picture is shot from behind, it is still very much a portrait of Fellini. You don’t have to be too literal when photographing people. Photography is not a factual, but a descriptive language. You must translate the scene visually and emotionally. This picture captures very much who Fellini was. He seems to be dancing gracefully, exactly like one of the characters in his films. This was just one moment, one frame, but it speaks to something larger, which is why it has become iconic. That’s what you’re really trying to do with a portrait, capture who the person is; get a glimpse at the essence of who they really are. Even if someone is on set or in a costume or standing on her head, you have to see beyond that to who they are.” (MEM, Seen Behind the Scene, Phaidon, 2008).

And with her photograph of The Cast of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, Oregon, 1975, Mary Ellen captured the frenetic dynamism of tension and claustrophobic environment of the film in a single snapshot. ‘The cast was gathered together after a scene. They were shouting at each other and at something behind me; I don’t remember what. Jack Nicholson leads the picture and makes it work, but there’s so much going on, with people looking in different directions and reacting to each other. There’s a palpable group energy, and yet the image still uses the space well and has depth. It’s not perfect; there’s a guy hidden in there, but that shows it was a natural situation.’

Another photograph that we feel encapsulates this notion is her photograph of ‘Mike Nichols with Meryl Streep, Silkwood, Texas, 1983’. Streep plays Karen Silkwood, the plutonium-processing plant employee who was killed in a suspect car crash as she drove to talk about safety violations with a New York Times reporter. The double portrait has Streep and Nichols seated at a booth in a diner. Streep is in profile looking past Nichols who sits facing us, the viewer. Streep, lost in thought, appears weighted down – possibly by the physical and mental strain of such a demanding role – almost exemplifies how Karen Silkwood must have been wrought by her decisions to come forward about radiation leaks and other hazardous practices within the nuclear plant workplace. And then we have Nichols, confidently glaring at us beyond the picture frame, representing the establishment and authority which challenges us to question and consider the story of Karen Silkwood and the beautifully crafted and nuanced performance by Streep.

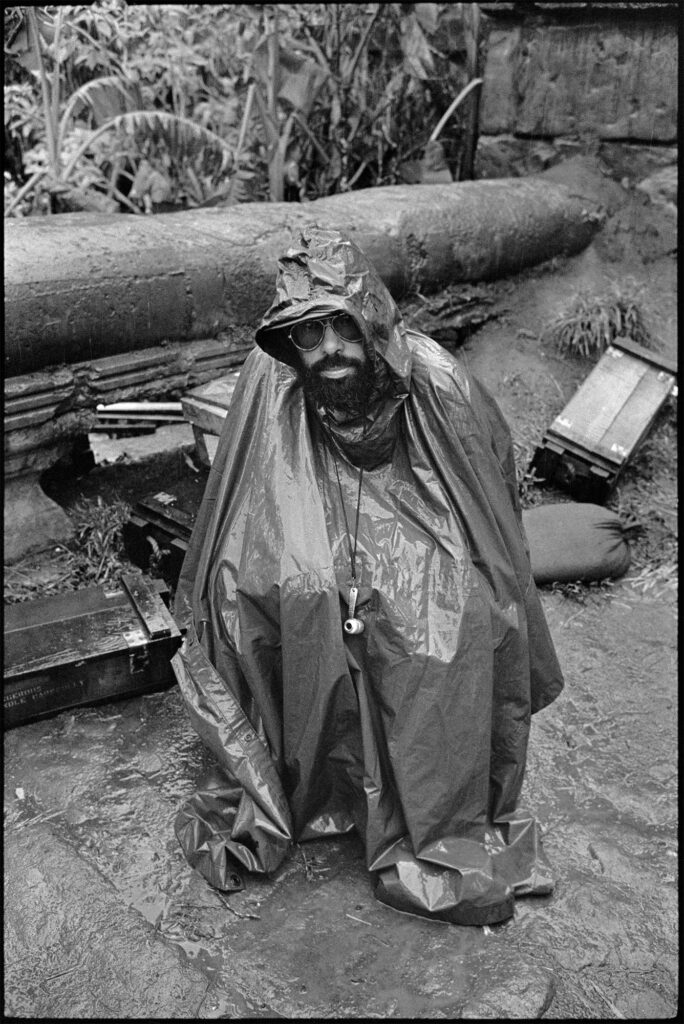

Gary has a particular fondness for Francis Ford Coppola from his role as Dracula; however, what ignited a desire to work with him was Coppola’s masterpiece, Apocalypse Now. More extraordinary than the film itself, is the behind-the-scenes footage which was recorded by Francis’ wife, Eleanor and featured in her documentary Hearts of Darkness – A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. The documentary chronicles how bad weather, health issues and increasing costs almost derailed the production of the film and could have possibly destroyed the career of Francis Ford Coppola. Mary Ellen Mark’s photograph, Francis Ford Coppola, Apocalypse Now, Pagsanjan, Philippines, 1976 depicts him sheltering from the unrelenting rain that contributed to the troubles of an already beleaguered shoot. The photograph exemplifies the conditions the director and actors faced but illuminates the exhaustion, frustration, and anguish as to whether the film and his career would be washed away by the rain.

Lastly, we wanted to discuss the portrait of Dana & Christopher Reeve, New York City, 1999 [See page 72]. There is not a more beautiful portrayal of the power of love. Dana had devoted her life to caring for Christopher after his near-fatal horse accident that left him paralyzed in 1995. Their bond was so strong that the doctors credited her for Christopher’s years of ‘borrowed time’ after the accident. As if she was his ‘medication’. Reeve may have been Superman, but Dana’s resolve, care, patience, love, support, and optimism was superhuman.

Mark was obsessed with photography, the process, the cameras, but most importantly, the subject and how to convey its story. We relate to that on a fundamental level. I have spent years studying photography and only recently begun to express myself with it, and Gary has observed and interpreted the characteristics of individuals through countless roles and a passion for all things cinematic before or behind the lens whether film and photography. It’s why Mary Ellen’s photographs captivate us so wholeheartedly.

Coincidentally, Mary Ellen is as responsible as Richard Miller for our fateful introduction. As Gary puttered around his home in Los Feliz wondering who took the photograph of Elizabeth Taylor and James Dean that early Saturday afternoon, he looked up at the first photograph he had ever acquired, Mark’s, ‘Fellini on the Set of Satyricon’. As he had acquired the print from Fahey/Klein, it’s what led him to return to the gallery to seek out an answer. He just never expected to find the answer, acquire the photograph and eventually get so much more!

Photographs by MARY ELLEN MARK

©️Mary Ellen Mark, courtesy of The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation/Howard Greenberg Gallery

Words by GISELE SCHMIDT & GARY OLDMAN