Words by CLINT BENTLEY

Co-writer and director of Train Dreams, Clint Bentley, celebrates an American New Wave movie that showcases a beautiful paradox and resonates through the decades.

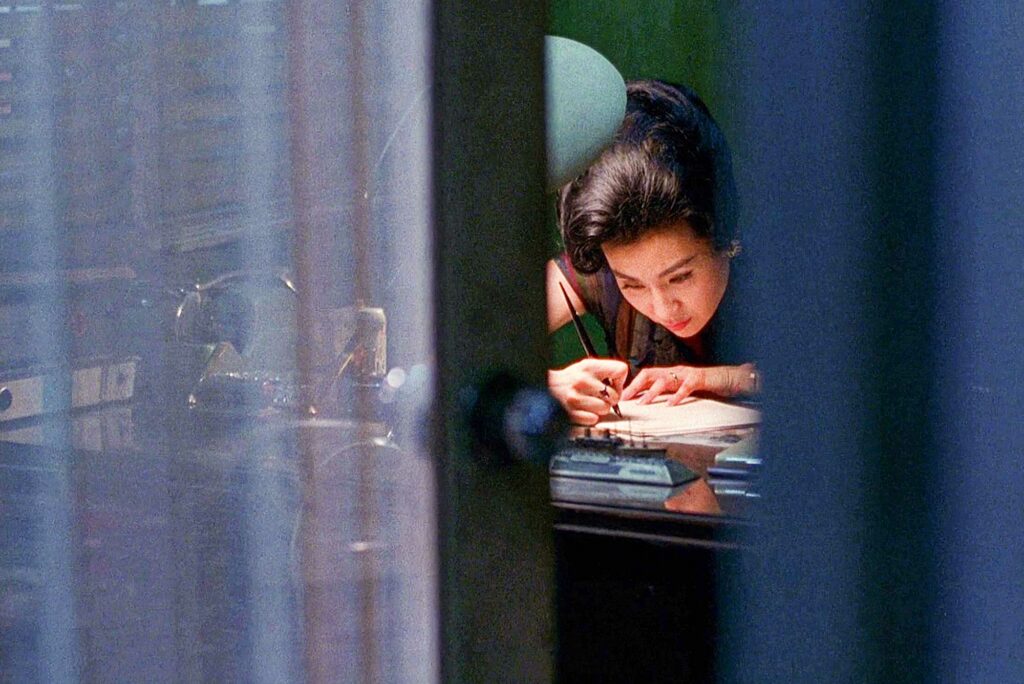

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (1975)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was the first film that really changed me. I probably saw it way too young – in seventh grade – about 12 years old – but that’s also part of why it was so impactful. I was having a terrible time in school: bullied, feeling out of place, learning for the first time that the world was not inherently fair. Then I saw Nicholson try to rip a sink out of the floor to throw it through a window and escape his confinement. And in that moment I was saved. I’ve carried that moment, along with the rest of this incredible film, with me ever since.

I grew up on a ranch in Florida. We only had three TV channels and so I watched a ton of movies, mostly with my mom. She loved American movies from the ’60s and ’70s and so that’s what I loved, too. Movies taught me about life. Steve McQueen, Clint Eastwood, Jack Nicholson – watching these men struggle helped me navigate those years. When I first watched Cuckoo’s Nest, I was moved so deeply by McMurphy – in a position where everything is stacked against him, but never losing his spirit. Never letting go of his passion for life. It opened me up as a person and, looking back, it set the tone for the types of films I one day hoped to create. There’s a deep humanism that runs through the film. A love and an understanding for its characters who are all trapped in an oppressive system. The older I get, the more that resonates with me.

The craft of the film is also so striking and so beautiful. It’s amazing to see how Milos Forman achieves this magical combination of intention and openness. It’s a beautifully written script that’s always taking the audience somewhere, yet so gently that many moments feel totally improvised. As if a camera just happened to be there when something happened. I know now what a rare and difficult balance it is to strike as I’m constantly trying to find it as a filmmaker. I’ve been so inspired by this approach. Of trying to create what might be closer to a theatre troupe and letting scenes play out before a camera in hopes that we might achieve the feeling of life, with all of its beauty and surprises. When you get lucky enough to find that balance, some magic happens. Moments appear that you never would have been able to dream up. Moments that come to define your movie. The whole film comes to life and you feel more like you’re discovering it rather than creating it.

Cuckoo’s Nest is also a film that allows itself to make mistakes. There are moments that I think the film could probably have been fine without – moments that, in and of themselves, you might not have missed had they been left on the cutting room floor. And yet that shagginess is part of what makes the film so lovely. It helps give it its personality. Like the characters in the film itself, its ‘flaws’ are part of what helps reveal its spirit.

In a movie full of unforgettable moments, one scene that has always stayed with me is the baseball game scene. Nurse Ratched (the incomparable Louise Fletcher) won’t let the guys watch a baseball game on TV. So McMurphy, in an act of defiance, pretends that he’s watching the game, acting it out for the guys. What starts out as something juvenile and a bit silly slowly takes on more resonance and depth. The other patients start to gather around him and he narrates the imaginary action with such conviction (yelling over the piped-in ‘calming’ music, no less) that these lost and bullied men momentarily believe in the game. They get lost in the performance and, more movingly – for this moment at least – they’re free. It’s an incredible performance from Nicholson, in the midst of a company of amazing performances. But more deeply, it’s a moment of rebellion and solidarity. A moment that illuminates the power of imagination. Of play. Of making art in dark times. It shows the power of art to foster resilience, endurance and to even be a protest in its own way.

There’s a melancholy to Forman’s film. It’s not only inherent in the story, but it suffuses through the filmmaking itself. From the look of the cinematography to the strange, haunting score that always seems to wander in from around the corner. And yet hand-in-hand with that melancholy is a deep love and appreciation for life. I leave this film and I’m just very thankful to be alive, to be able to walk around. It reminds you to revel in the little moments. Having a beer at a baseball game. Going out to meet a friend. It reminds you what a blessing it is just to be alive.

A more recent inspiration from this film came when considering how to approach an adaptation of a piece of literature – especially one as iconic and beloved as Train Dreams. Having just adapted this novella, I now know the responsibility and the fear inherent in the task. It’s a delicate process. The film must be able to stand on its own, whether the audience has read the book or not. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest releases itself from the source material while always honoring its spirit. Despite the liberties taken with the text (and despite Ken Kesey’s hatred of the film), it’s hard not to see the reverence that Forman had for the source material and for what it could communicate about the human spirit.

The ending of the film still bowls me over every time I see it. The way tragedy and triumph somehow exist in the same moment. The element of rebirth inherent in the story. It’s a catharsis I still get shaken by every time I experience the film. One of the beautiful aspects of great art is that it can give us this emotional release. It seems to be something we’ve needed as long as we’ve been human – from the early tribal ceremonial experiences, up through Ancient Greek theatre, into today where most of us get it in the cinema (I’m sure there will be some other unimagined form one day). It’s a rare and special thing when a film can pull us into a story, take us on a deep emotional journey and, in the process, transform us. The pieces of art that achieve this resonance and depth become timeless. We hold onto them. It’s why we still read Don Quixote. It’s why this film will never go out of style. Despite moments that end up feeling dated or from another time, there’s a universality that we hold onto. Something that we’ll return to over and over to help us get through the dark times, whatever form they may take.

All images © Amazon MGM Studios

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) received critical acclaim, and is considered by critics and audiences to be one of the greatest films ever made.

Train Dreams is streaming now on Netflix