Words & Interview by ARIANNE PHILLIPS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

The Oscar-winning vanguard costume designer who created the sartorial world of Oz tells Arianne Phillips about juggling numerous projects, ensuring he stays joyful and his belief in creating opportunities for the next generation of talent.

Paul Tazewell has profoundly impacted theatre and film. As well as receiving an Oscar for his work on Wicked earlier this year, he also won the Critics’ Choice Award, the Costume Designers Guild’s Excellence in Sci-Fi/Fantasy Film award, the NAACP Image Award, and the Innovator Award from the African American Film Critics’ Association, underscoring his critical role in bringing the fantastical world of Oz to life. Additional accolades include an Academy Award nomination for West Side Story in 2021, an Emmy for The Wiz! Live, and recognitions for his contributions to Harriet, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert.

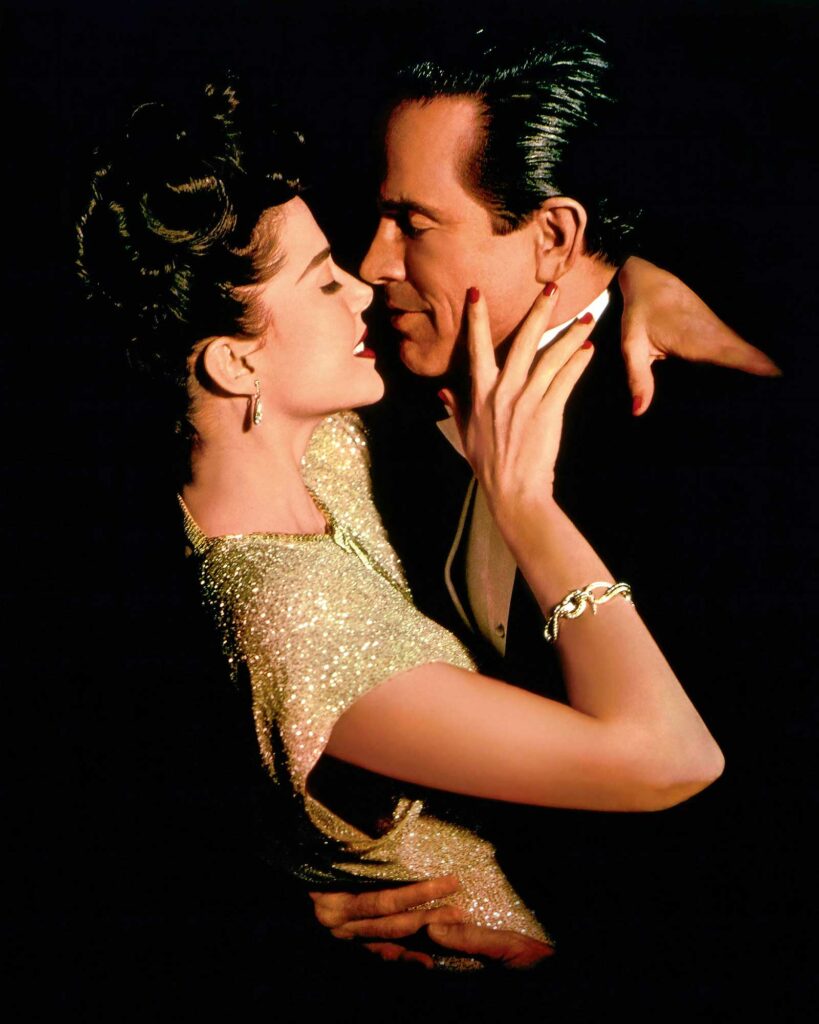

On Broadway, Tazewell has been nominated for a Tony Award 10 times, and won twice. Earlier this year, his costumes for Death Becomes Her – currently on Broadway – won him the 2025 Tony Award. Most notably in 2024, his designs for the production of Suffs earned him a Drama Desk Award and also a Tony nomination. His revolutionary designs for Hamilton won him a Tony Award in 2016, further establishing his reputation in theatrical costume design – and inspiring generations of young people to go to the theatre.

Throughout his career, Tazewell has earned multiple Lucille Lortel Awards, Helen Hayes Awards, and additional accolades from the Costume Designers Guild. His dedication is also evident in his collaborations with The Metropolitan Opera, The Bolshoi Ballet and The English National Opera.

Educated at New York University and the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, Tazewell has shared his expertise as a guest artist at these institutions and served on the faculty at Carnegie Mellon University from 2003 to 2006. Based in New York City – although probably rarely there these days – Tazewell continues to inspire and shape the future of costume design, bringing life to a rich tapestry of characters through his artful and intricate designs.

AP: I’d love to start at the beginning, and understand where you grew up, what family life was, and at what point did you get inspired to pursue costume design?

PT: I grew up as one of four boys in Akron, Ohio to my two parents. My mother was the daughter of a university educator and a pianist. My grandmother studied at Oberlin and then at Wesleyan, and then she taught piano. My mother was an artist and an educator as well. So it set up an environment that was very creative. That was very inspiring and also necessary for me, because I think much of what I experienced as a child informs how I do my work, even to this day. Because my mother also practises as a group therapist I had that interest in what makes people tick; why people do what they do; why they wear what they wear, essentially; and how they create their own individual character; how they represent themselves – it became a big part of the language that I now use as a professional designer.

AP: I really relate to that. In these conversations that I’ve been having I’ve learned that so many of us, in these early years as children, whether it’s community theatre or an artistic environment, were really encouraged to express ourselves in multiple different ways. It’s a beautiful ability to inspire your children to look at life through this amazing lens of storytelling.

PT: It was really theatre that drew me in. The community building, the joining together in creating a production, for the single goal. The drive to recreate that environment where I could excel; where I was engaging with other people that were very creative. It’s how I collaborate even today. What it takes to be a costume designer, it’s inclusive of all those things that I love to do. I love fabric, and what fabric does, what you can do sculpturally with fabric. I love the drawing and painting and coming up with different ideas, whether it’s around space and in an environment, or it’s just specific to, ‘What is a character going to look like?’ I love working with very talented tailors, dressmakers and other craftspeople in creating the different costumes. I love engaging with directors, and figuring out what the point of view of the story is going to be, and also with actors, and that intimate place of finding that individual character.

As an undergraduate, I really wanted to be a musical theatre performer. But because of the time that I was coming up, I wasn’t seeing people that looked like me getting the roles that I wanted to play. And so I made a conscious decision to pull back on performance, and really lean into the world of costumes, because I could then design for any kind of character. Now having practised as a costume designer for about 35 years – I’m so grateful that that was my decision. Last year is a testament to that. All of this love, and all of the accolades that I received. But also it’s made for just a very rich career in a way that I don’t know that it would have been if I had been a performer. And being able to practise my art in live performance, as well as film, television, opera and ballet – there are so many different venues that I’ve been able to practise in, and that has made for a very rich career as well.

AP: In 2002 you had your first opportunity to work in television with Elaine Stritch at Liberty. Then in 2008, just six years later, you designed a film with Spike Lee. What’s your process for working between theatre, opera, ballet, television and film?

PT: Whatever I’m designing, I’m always myself. So my sensibility remains intact. I’m very aware of the different venues as it relates to scale, or as it relates to a sense of reality. Something like Henrietta Lacks, you are trying to give the illusion, or create these characters that feel like real people that you would see on the streets, or that you engage with wherever you are. You need to find that quality of reality. And then also be specific about who they are as characters – giving them a backstory, giving them a reason to be wearing what they are wearing. So I’m able to do that as well as operate with a mind towards poetry, with a mind towards the world of musical theatre is its own thing. On something like West Side Story, you’re balancing the function of clothing that needs to move and dance and look of a certain energy and beauty. And you also want for the colour palette that you use to mean something. You want to be specific about each of the characters and it has to feel like real ’50s New York. Which is different from Wicked where it’s completely made up, but you have to establish what those rules are in order to be consistent about what this world of Oz is. So it’s always shifting and changing, and I’m completely in love with that – having that broad opportunity to be able to design in many different ways. But with all of those different versions of genres, of performance, of entertainment, I’m the constant. You can see through my work – you know, my draw to strong colour, to detail, to character specificity. All of those play within each of the genres of performance.

AP: How wonderful it is to be able to approach these well-loved stories, and to be able to be intimate with them on film. Your work consistently has beautiful details, and I think it really shines in the room as well on camera. What do you look for when deciding to work on a project? What excites you?

PT: It’s always informed by the director that has asked me to design the production. When we were starting out as young designers, you’re about developing and nurturing creative relationships that will get you to the second job or the third job. You’re working as a freelance designer so that becomes very practical. You’re pragmatically accepting jobs so that you can maintain a life. But then you have these creative relationships where they really do feed you as a creative being. The familiarity, working on the second production and the third production, is really gratifying because you can learn from what you’ve done. So much of the work we do, we can only do it really well when we trust the people that we’re working with. When we have the trust of the director, the actor, the designer, you have to create a bond.

Early on, I was just saying yes to as much as I could actually take on. Whether it was a great moment of design, at the very least it gave me another opportunity to practise my craft. And it gave me the opportunity to work with other people that I’ve never worked with. And I learned from that. Walking through costume designing in an abundant way, it’s had a really positive result. And then you come upon a Hamilton – which was definitely a marker in my career and hit the zeitgeist, and really launched into the world – that meant that I was more visible to more people, whether that was theatre people or film people. That was one of the big reasons that I started working with Steven Spielberg on West Side Story and I did Harriet. One thing feeds off another. The universe has been very generous in that way, in offering opportunities.

AP: Speaking personally, being nominated for an Academy Award alongside you this year, it was not lost on me how historic and important it was for your nomination and your win for Best Achievement in Costume Design for the Oscar [Tazewell was the first Black man to win the category]. Can you reflect for us a little bit about that moment in particular?

PT: One thing that was very special

about this year, it was also where I turned 60. I’ve been a professional costume designer since 1990. That’s a huge body of work that I did prior to this amazing moment. One of the things I was thinking is, ‘I’ve been here doing this for all of these years, and you guys are just catching up!’ But also just being grateful. For me, it was really glorious to then be able to have all of the experiences surrounding it. But I needed everything that led up to the designing of Wicked to happen, because then I could make use of it. I could be a master of how to orchestrate what this vision would potentially be, and what [director] John M. Chu was looking for; matching what [production designer] Nathan Crawley was doing. To then be acknowledged for it in such a loud way was really beautiful. And to then say, ‘Indeed, thank you. I’m a first’…

Ruth Carter and I go way, way back to when I was at North Carolina School of the Arts. She was the first Black woman to receive an Oscar for costume design, and then to be able to stand alongside her and be represented in that way is hugely meaningful. Entering into this career, you know, so often I’m sitting at conference tables where I’m the only Black face at the table. For so many years, I was seen as the right designer for stories about people of colour. First off, it was stories about young people of colour on the street, and then it became about people of colour in a broader sense. Now, finally, I can be seen as a person who is just a storyteller. And that’s hugely meaningful. What my priority is now, is that 10-year-old that looks like me and is struggling to figure out what they want to do, or how they want to create, or how they want to live their life. If I can stand as an inspiration for that kid, for that ‘me’ of today, then that is everything that I want. It’s why I’m on Earth – to power life forward.

AP: You’ve established a Paul Tazewell Scholarship fund at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, your alma mater, so you are putting that into action…

PT: As we all know, it’s going to take a lot to continue the support of young designers and young people that are entering into the world of the arts. It was much easier when I was coming up. There were many more programmes, art schools, ways of expanding as a young person. And that’s just becoming harder and harder. If I can be a part of that, that’s really important.

AP: I really loved that during the award season you used social media to introduce all your craftspeople, highlighting their work, and all these amazing, talented hands that help us bring our work to life.

PT: It’s another huge priority for me, because not everybody is going to be a designer. Shining a light onto the team that makes it happen is so important for me. I can’t work in a vacuum. It doesn’t just miraculously happen. They’re not elves. They’re working very hard to deliver amazing garments. It’s so very important to make sure that people know about them. When I was finishing up Wicked, I was just starting a design for Sleeping Beauty, a story ballet for the Pacific Northwest Ballet company in Seattle, as well as Suffs and Death Becomes Her. So I was working on the three designs as we were finishing up Wicked with three different teams.

AP: How do you manage it all?

PT: When I was doing Wicked, because of the scope, I had to clear the plate. I’ve heard of other designers taking on two films at the same time. I’ve never tried to do that. But you just have to be really diligent about how you schedule, and what you say yes to. And making sure that you have the support. I like the abundance of creating, and I’ve lived through lots of chaos in that process. At this stage in the game, I choose to have it be a little less crazy. You know, as full as possible, but as stress-free as possible as well! I’m very grateful because this is not an easy career to be a part of. It is a challenging road to make this decision with a lot of compromises, whether it’s about time and family, or whether it’s about how you live. You have to create that love of what you’re doing so that you will give over to what is required to do it, and to do it well.

I definitely respect what this calling is, and hopefully I can always be joyful in doing it, and create other opportunities for myself and for other people that are joyful.

Words & Interview by ARIANNE PHILLIPS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

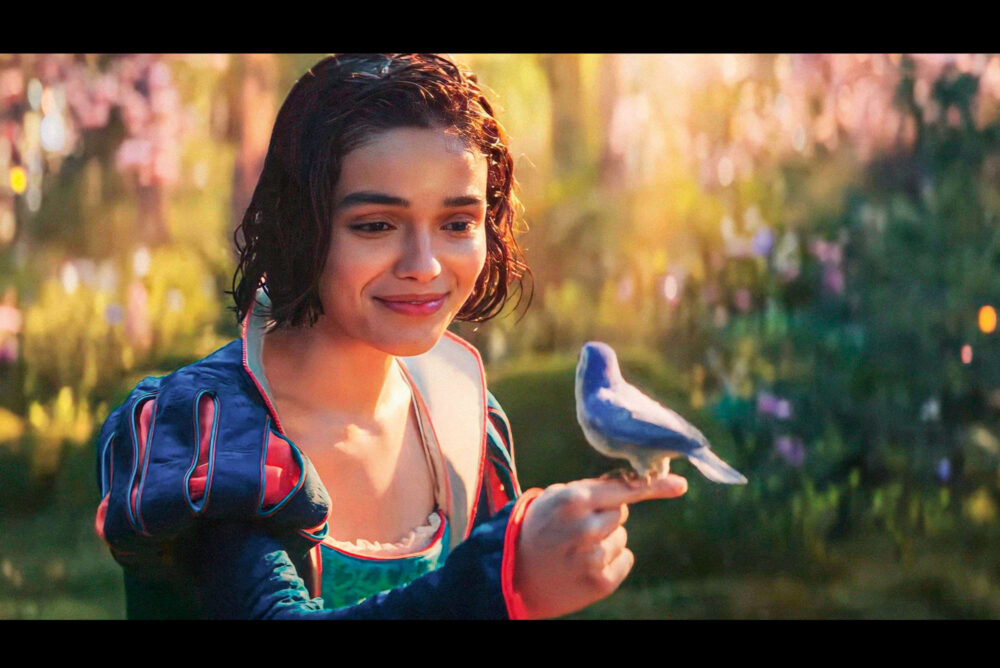

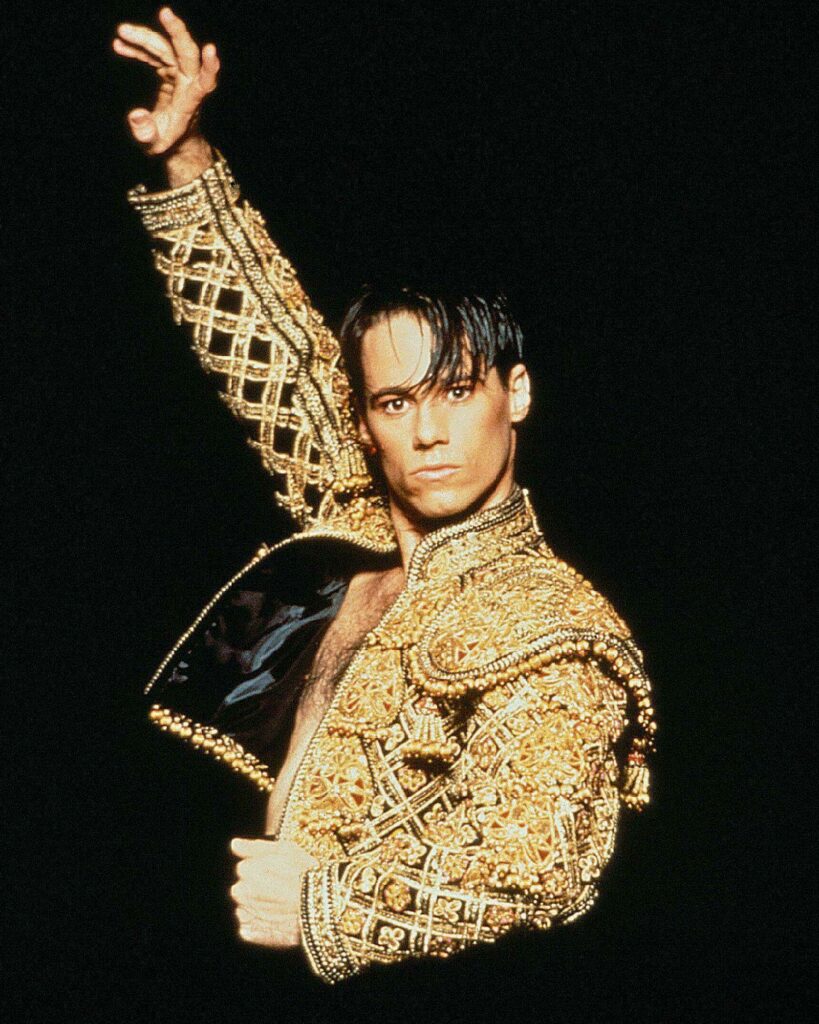

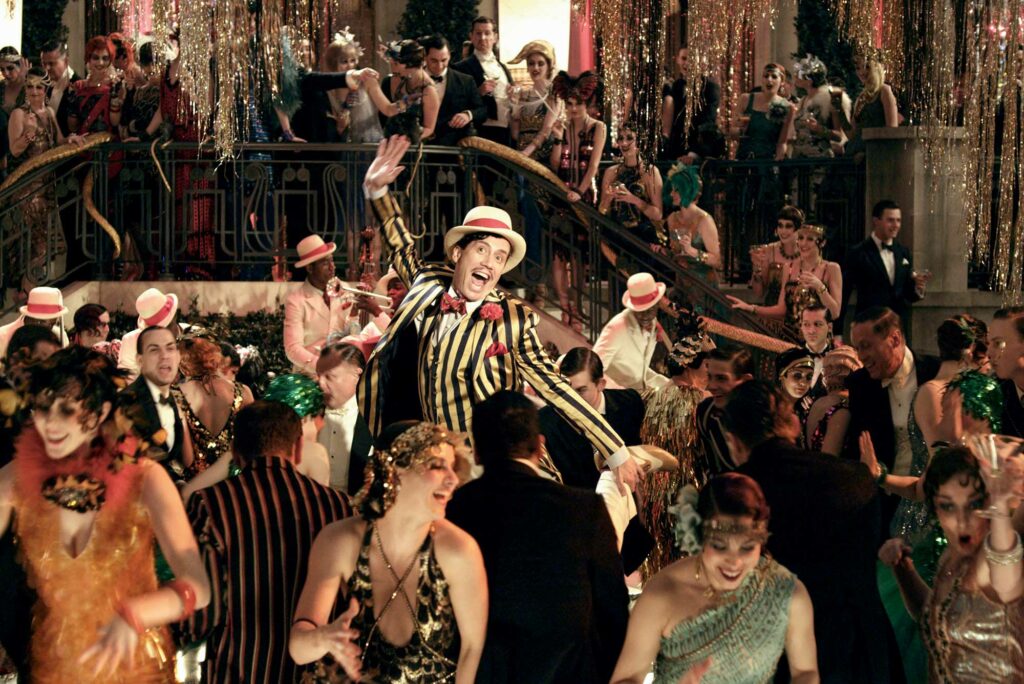

Carol / Caravaggio / Far from Heaven / Gangs of New York / Orlando / Snow White / Velvet Goldmine