Words by KRYSTY WILSON-CAIRNS

The Academy Award-nominated screenwriter of 1917, Last Night in Soho and The Good Nurse, Krysty Wilson-Cairns, salutes a series of mishaps that honed Francis Ford Coppola’s unfinished espionage film into a perfect classic.

The foundational years that formed my sense of myself as a writer took place mostly in isolation. Initially in a bedroom, then in a series of bedrooms. Sometimes perhaps punctuated by sessions in the real world, cocooned from it in a pair of noise-cancelling headphones. This useful isolation from the world became, more than anything, a badge of validation. ‘Look! How she squints in the daylight. Gaze upon her ghostly pallor.’ I was serious. I was a writer.

Because at the end of the process I would inevitably emerge back into society with something to show. I would emerge with a screenplay. And without a screenplay, what would the directing students direct, what would the acting students act? As a screenwriting student, I knew the truth. No matter how much the auteur theory was hammered into the directing students and the art of improvisation fed to the actors, the screenplay was key. I understood my work to be something immutable. Sent out in the world complete. Like a painting or a photograph.

At that time, my favoured texts were the ones that worked hard to get the win. The sharp, twisty thrillers that showed a masterful corralling of the audience’s attention from beginning to end. Those films that took you one way before pulling the rug out from under you. Most of all, I loved the paranoid thrillers that came out of the USA in the ’70s. Three Days of the Condor, The Parallax View, Klute… films that spun the audience a web of lies and confusion before pulling out the rug from under them and saying, ‘No, this is how it really is.’ Paranoid, anxious, tightly wound. (In no way a reflection of my mind at the time…)

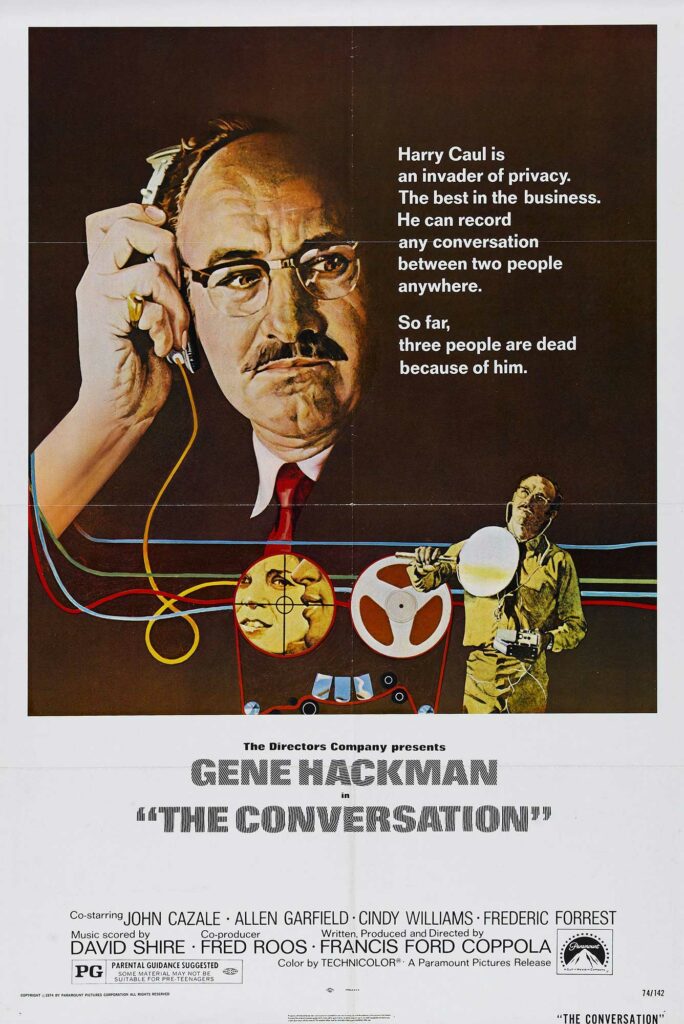

Above them all stood The Conversation. A sparse, taut, tense thriller starring Gene Hackman alongside the late, great John Cazale (can any actor have given so much in such a tragically short career?). With cameos from Frederic Forrest, Robert Duvall, Harrison Ford, Teri Garr and Cindy Willams, The Conversation was at the apex of the talent that defined the New Hollywood of that decade.

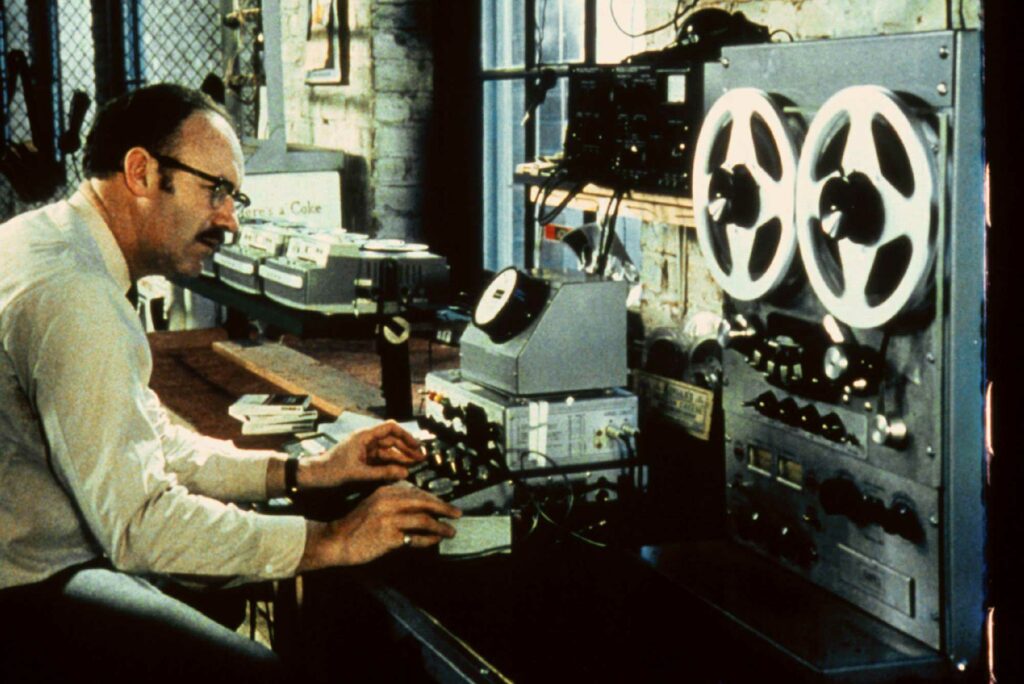

Written and directed by the great Francis Ford Coppola, if any film was evidence of the primacy of the screenplay it was The Conversation – 112 minutes of terse, tight character action. Hackman (never better) plays Harry Caul, a reclusive, emotionally closed private investigator who is hired by a mysterious client to record a seemingly mundane conversation. Inevitably the job is not as simple as sold and Harry is left contemplating the morality of his work, along with his role in the world. What feels like very low stakes to begin with soon becomes a matter of life or death.

But that’s not why I loved it. I loved it for the exactitude of the writing. The entire plot hinging on a glorious pay-off at the end that relies on, of all things, intonation of key dialogue. ‘He’d kill us if he got the chance’ is the line you’ll remember from this film. It’s what everything leads towards and, despite its intonation being somewhat lost in the multiple languages in subtitles on the screen during its premiere at Cannes, it still won the Palme D’Or that year – and rightly so. Could anything be more writerly? More illustrative of the primacy of the script, of the screenwriter’s intentionality? That Coppola, the writer, pulls us through his world for almost two whole hours before pulling it all out from under us with something so simple as the emphasis of a pronoun! Except, of course, he didn’t… well not exactly.

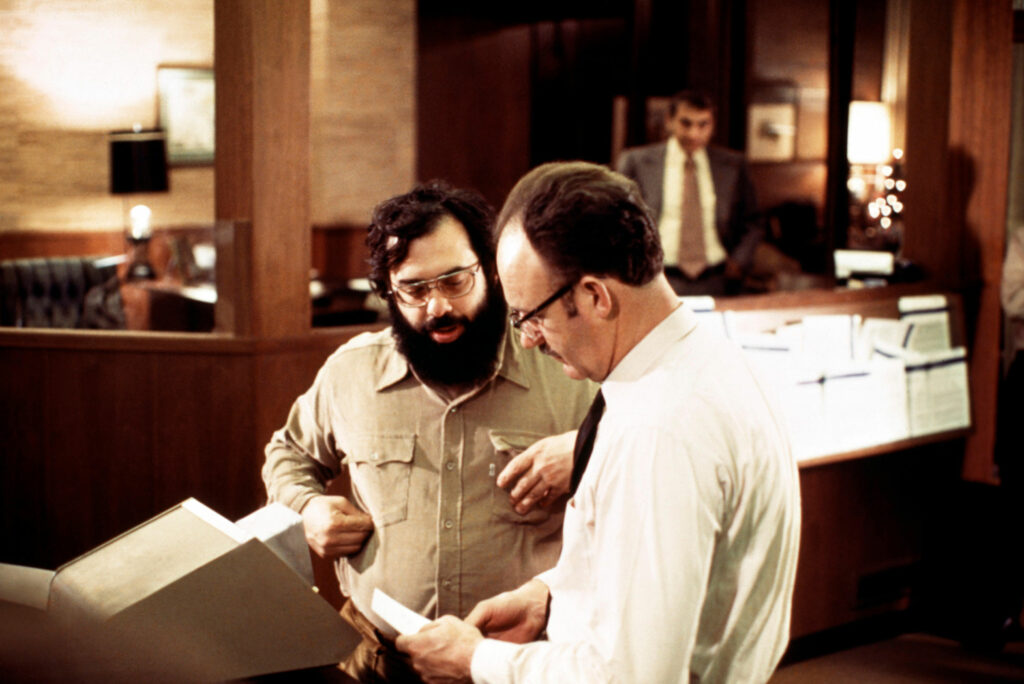

Imagine my surprise when at a BFI screening and Q&A, Walter Murch, the film’s sound designer and editor, suggested an alternative. In Murch’s retelling, an entirely different version of Coppola’s film was originally planned: one that stuck closely to a bloated 157-page screenplay. As fate would have it, Coppola was called early to start shooting his next studio tentpole, The Godfather Part II, leaving the much smaller, more experimental The Conversation with 78 scenes yet to be shot. Seventy-eight!

And so, Coppola flew off, leaving the existing footage in the very capable, but rather green, hands of the young Walter Murch. Coppola just told Murch: ‘Do what you can.’

None of the scenes in which Harry tracks down the girl, gets all the answers and discovers the real story had been shot. So, the film’s narrative, as it existed in celluloid, in stacked 35mm reels in the editing room, currently had no denouement. Faced with a film missing over a fifth of its screenplay, with little chance of additional shooting days from the studio, and with his director on the other side of the country, Murch did the only thing he could. He tore up the screenplay and worked with what he had.

In one ingenious move, Murch completely redesigned the film’s story and structure. The film’s pivotal scene takes place in the aftermath of a drunken party. The woman Harry has slept with steals the vital recordings, forcing Harry into action and the film towards its conclusion. Only, the way the scene was written (and filmed) was originally much more throwaway – the woman’s role in the film was to validate Harry’s distrust, not further the plot (she originally only steals plans for a recording device for Harry’s competitor).

By thrusting a minor character into the thick of the plot, Murch consolidated the two storylines, and all it took was a single additional shot – a cutaway of Harry’s arms revealing the stolen tape reels. Using Hackman’s brother as a stand-in, Murch recreated the set in a corner of a stage being used by another film that was shooting at the time – Chinatown. They didn’t even have to pay for the camera hire. In that one move, an unwieldy, twisty, 240-minute thriller becomes a tight, sparse, sinewy sub-two-hour masterpiece.

You might ask, as a writer, what of the excised material would I be interested in seeing restored? The answer: none of it. From my current perspective, as one who has emerged from the cave, and who has been on set during the filming and in the edit of all the films I’ve written, I’ve been able to experience first-hand how much the story evolves and needs to evolve during the filmmaking process. I now know all too well that the primacy of the screenplay (much like the auteur theory) is a fallacy. An illusion, to justify those weeks spent in the dark. Typing. Alone. Who am I to assume that whatever motivation I conjured while sitting in my pyjamas will ring true after an actor has brought life to it in front of a camera years later.

If it’s not in the film, it doesn’t exist. The casting, the designing, the actual shooting takes that immutable thing – the screenplay – and whittles it, hones it and sometimes just negates it for something else truer, which is what we see on screen. And that line that I loved, ‘He’d kill us if he got the chance’ – that intonation that expertly shifts emphasis, turning a repeated, innocuous plea into a wilful declaration of violence? A happy accident. A mistake by the actor, marked on the day as a bad take, destined for the cutting-room floor, but that ultimately replaced the work of 78 unshot scenes of slow realisation with the time it takes to say eight words. I like to be efficient when I write, but this is a next level of genius, and a perfect example of the screenwriter’s mantra – show it, don’t tell it. Famous for going back and re-editing his own films, The Conversation was the one film that Coppola had always thought was ‘perfect, just the way it is’. Because of course, it is. It’s perfect. It may have come about through a series of mishaps and the incredible talent of Murch’s editing, but it couldn’t be any other way.

Words by KRYSTY WILSON-CAIRNS

The Conversation (1974), Paramount Pictures, written and directed by Francis Ford Coppola, starring Gene Hackman. Available on Apple TV