Words by JANE CROWTHER

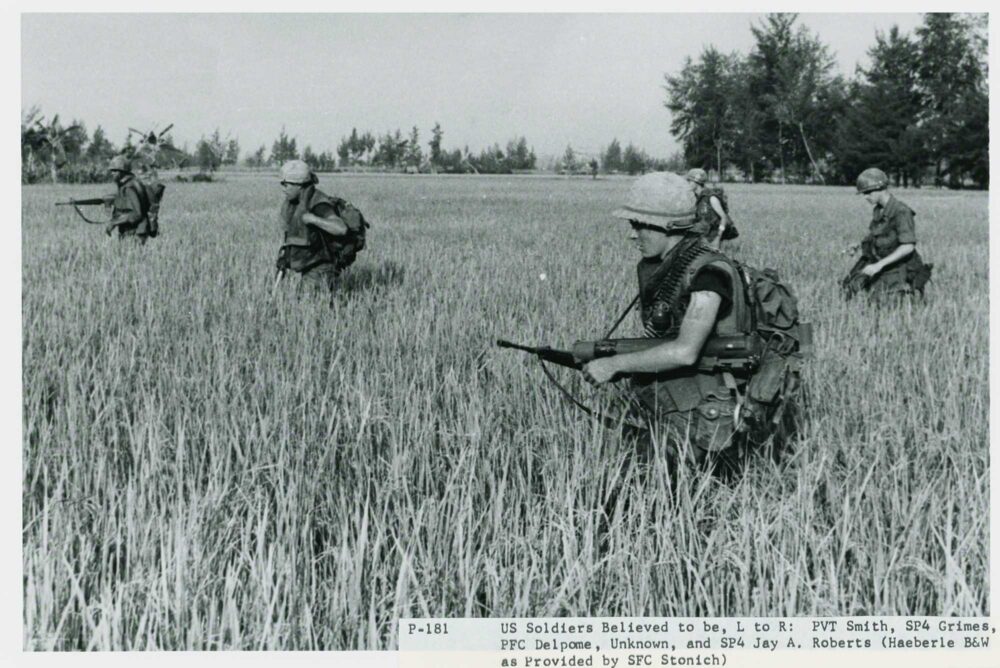

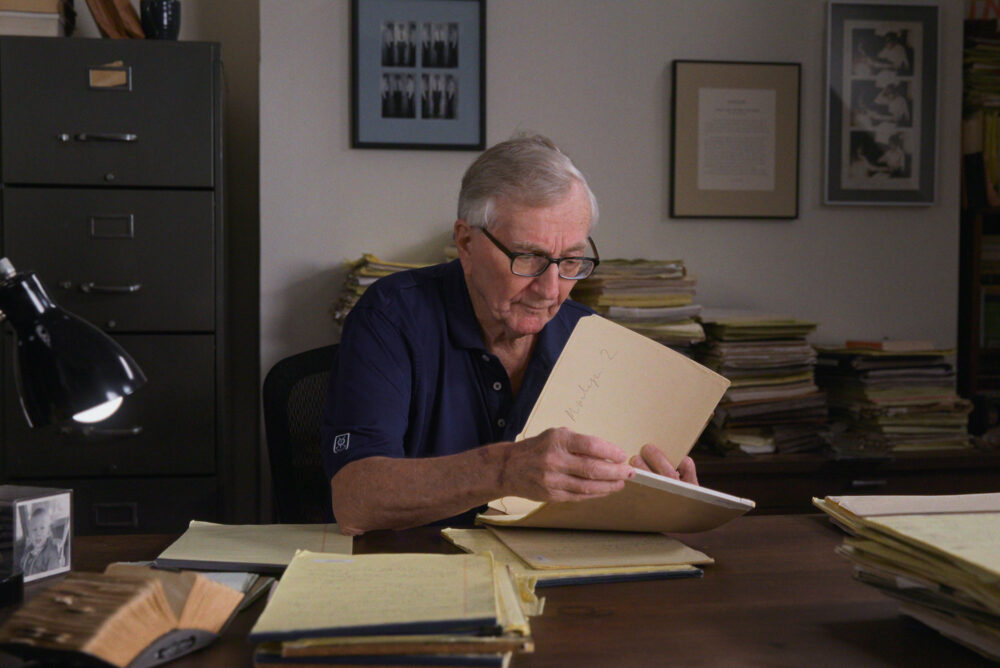

In these days of AI, fake news and the decline of print media, it’s something of a thrill to watch Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’ study of a Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist as he looks back at his scoops and old-school investigative reporting. Now in his eighties, but still a pill on the phone to his sources and scribbling longhand on countless yellow legal pads, Seymour Hersh is renowned for breaking the story of the US military massacre in My Lai during the Vietnam War via dogged research, nosy-parkering and tenacity – and he’s continued to expose corruption, power play and cover-ups in the decades since. Such a thorn in the US government’s side that White House tapes caught Nixon calling him a ‘son of a bitch’, ‘Sy’ is an entertaining subject, and a reminder of disappearing skills and industries.

In charting some of Hersh’s most famous stories – including those interweaved with Woodward and Bernstein over the Watergate scandal, and the torture at Abu Ghraib prison – the directors chart some of the US government’s darkest secrets and plots straight out of movies. One of Hersh’s leads took him to the CIA’s attempts to create a real-life Manchurian Candidate using LSD, his folly in believing he’d found love letters between Marilyn Monroe and JFK is unpicked, and his current unveiling of atrocities in Gaza keeps him horrified. And while Hersh reveals his methodology (he spent an entire meeting making small talk with military top brass while transcribing an upside-down document on his desk), he also reveals his own story.

A working-class boy expected to take on his dad’s business, he developed an unexpected flair for writing, tearing up as he recalls a teacher taking him to the admissions office of the University of Chicago. Study led to work covering police beats and gangland slayings on Chicago local papers until he decided he wanted to write about more than ‘mass murders’.

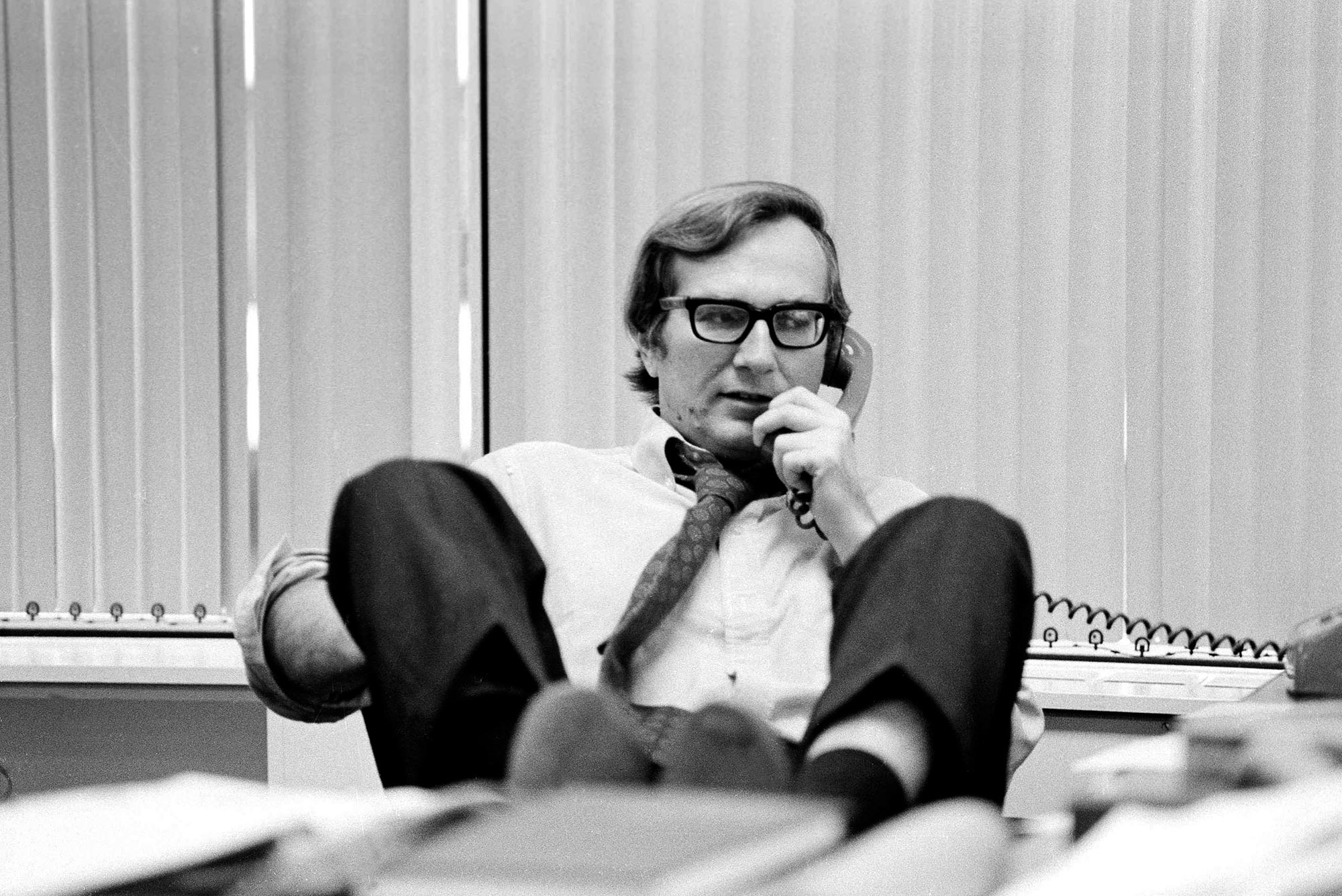

His tenure at The New York Times was during a period when newspaper print was impactful, stories typed out and sucked up tubes in the newsroom, journalists propped their feet up on messy desks while smoking and calling moles on their landlines.

That’s not to say that Cover Up is a nostalgia trip (though aficionados of archival presses churning out news print are well served), the film stays relevant due to the constants that remain throughout history. That power continues to breed corruption, and that someone needs to hold administrations accountable. The big question the film seems to ask is – with truth seeking, hard news reporters like Hersh, now a vanishing type – who will perform this role going forward?

Pictures courtesy of Netflix

Cover Up is in cinemas now